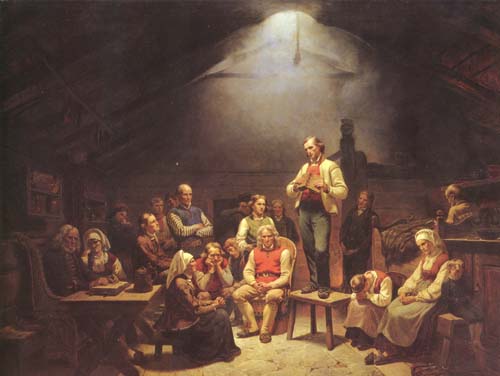

Yesterday's blog post, Lay Ministry: A Continuing Legacy of Pietism, began with the sentence, "Pietism was a raging problem among Lutherans in mid-19th Century America," and closed by pointing out that in Norway, "[p]olitically and culturally, religious liberty [had become] synonymous with lay participation in the functions of the Office of the Ministry within the congregation, such that, by the time of the first wave of Norwegian emigration to the United States in the middle of the 19th Century, not only was the practice of laymen carrying out the functions of the Pastoral Office culturally accepted, it was considered a political right." This was the result of Haugean Pietism which had coursed through Norwegian religious and political culture not more than a generation prior, and which was still at work reforming Norway's cultural institutions, as dramatic political and economic changes continued to occur there.1

Yesterday's blog post, Lay Ministry: A Continuing Legacy of Pietism, began with the sentence, "Pietism was a raging problem among Lutherans in mid-19th Century America," and closed by pointing out that in Norway, "[p]olitically and culturally, religious liberty [had become] synonymous with lay participation in the functions of the Office of the Ministry within the congregation, such that, by the time of the first wave of Norwegian emigration to the United States in the middle of the 19th Century, not only was the practice of laymen carrying out the functions of the Pastoral Office culturally accepted, it was considered a political right." This was the result of Haugean Pietism which had coursed through Norwegian religious and political culture not more than a generation prior, and which was still at work reforming Norway's cultural institutions, as dramatic political and economic changes continued to occur there.1Hans Nielsen Hauge died in 1824 a folk hero. In 1825, the first of several major migrations from Norway to America occurred, landing mostly in northern Illinois along the Fox River. By the third large migration, around 1840, Norwegians were settling in southeastern Wisconsin, and it is about this time that Norwegian Lutheran congregations began forming.2 The Norwegian settlers during the 1840's and 1850's were very closely "connected with the Church in the homeland, and they brought with them greater respect and love for the rites and usages of the Church of their fathers."3 Yet, prior to 1843, there were no pastors to serve them -- only Haugean lay preachers. Two Norwegian pastors, Dietrichson and Clausen, finally arrived, and did much work during these days in the Koshkonong and Muskego settlements, correcting the confusion wrought by Pietism, diligently securing deliberate and specific confessions of faith and intent from new members of a growing number of congregations, and working for greater unity among them. Rev. Stub joined them in 1848, and in 1850, with a great deal of groundwork completed under the leadership of Rev. Dietrichson, three pastors -- Clausen, Stub, and Preus -- along with eighteen congregations between Muskego and Koshkonong, Wisconsin, formed the Norwegian Synod.4

The situation was slightly different among the Germans. Pietism was nearly a century-and-a-half in the past for them, and time had carried them through Enlightenment Rationalism and ecumenical mergers. Elements of Pietism and Rationalism abounded among them, and, intermingled, were a great danger -- often being more subtle and insidious. German Lutherans had been in America since the early Colonial days, and this was largely the case among those in the East.

When the Stephanites landed in Perry County, MO, having emigrated from Saxony to escape various forms of religious persecution which resulted from the Prussian Union, they found that the seed of Lutheran orthodoxy existed in America and was already at work in the eastern States to purify doctrine and practice -- the Henkel clan in the Tenessee Synod and Charles Porterfield Krauth having begun the work of addressing error, and grown experienced in spotting its subtleties. C.F.W. Walther, after ascending to leadership of the Saxon Lutherans in Missouri, sought them out, resonating with their doctrine and their task (having himself been a Pietist at one time). On the other hand, in the Norwegian Church, Rationalism hadn't yet made any real inroads, nor had indifferentism generally grown into open ecumenism with the Reformed or with the Methodists (although it had among the Haugean lay preachers, at least in this latter case). The only real inroad made by Rationalism was a mild form borrowed from an early 19th Century Danish theologian named Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig -- "Grundtvigianism," or the error of elevating the Creed to authority equal with Scripture, and Baptism of the deceased to procure their Salvation. In fact, this issue was brought against Reverends Clausen and Stub in the mid-1850's, and they were found to have been teaching this error with Dietrichson all along. Stub confessed and retracted his errors, Clausen retired.5 As one can imagine, other issues abounded and were resolved, the constitution was reworded and improved, and as the Norwegian Synod grew, they grew more aware of their similarities with the Missourians and formed a positive opinion of them and their theology.6

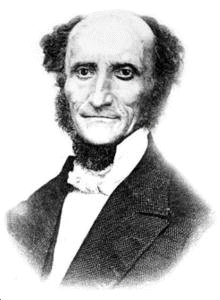

When the Stephanites landed in Perry County, MO, having emigrated from Saxony to escape various forms of religious persecution which resulted from the Prussian Union, they found that the seed of Lutheran orthodoxy existed in America and was already at work in the eastern States to purify doctrine and practice -- the Henkel clan in the Tenessee Synod and Charles Porterfield Krauth having begun the work of addressing error, and grown experienced in spotting its subtleties. C.F.W. Walther, after ascending to leadership of the Saxon Lutherans in Missouri, sought them out, resonating with their doctrine and their task (having himself been a Pietist at one time). On the other hand, in the Norwegian Church, Rationalism hadn't yet made any real inroads, nor had indifferentism generally grown into open ecumenism with the Reformed or with the Methodists (although it had among the Haugean lay preachers, at least in this latter case). The only real inroad made by Rationalism was a mild form borrowed from an early 19th Century Danish theologian named Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig -- "Grundtvigianism," or the error of elevating the Creed to authority equal with Scripture, and Baptism of the deceased to procure their Salvation. In fact, this issue was brought against Reverends Clausen and Stub in the mid-1850's, and they were found to have been teaching this error with Dietrichson all along. Stub confessed and retracted his errors, Clausen retired.5 As one can imagine, other issues abounded and were resolved, the constitution was reworded and improved, and as the Norwegian Synod grew, they grew more aware of their similarities with the Missourians and formed a positive opinion of them and their theology.6From the influence of pietism, from both pastors within the Norwegian Synod and its laity, the question of "laymen's activity" arose in the late 1850's, stirred for a few years, and finally broke into open controversy in 1860. The party in favor of "laymen's activity" asserted the following:

- Laymen should have the right to teach and pray publicly, (1) because they belonged to the universal priesthood of believers; (2) because Christian brotherly love demanded it; and (3), because it was the practice of the early Christian Church.7

At loggerheads over this question for two years, finally at the 1862 Convention of the Norwegian Synod, C.F.W. Walther was invited to address the question, in hopes of helping them to find a resolution. He did so by dividing the question into three parts:

- (1) the spiritual priesthood of all believers [Universal Priesthood]; (2) the special office of the ministry in the congregation established by God [Office of the Ministry]; and (3) how necessity knows no laws, hence supersedes the regular order in this matter [emergency situations].

In regard to the first... Paul, in Ro. 3:2, declared of the Old Testament Church, or believers at that time, that "unto them were committed the oracles of God." They were, therefore, the possessors and the stewards of God's Word, or the ministry. When factionalism arose in Corinth between the followers of Paul, Apollos, and Cephas, and each faction gloried in its leader, the apostle said to them: "Therefore let no man glory in men, For all things are yours; whether Paul, or Apollos, or Cephas, or the world, or life, or death, or things present, or things to come; all are yours; and ye are Christ's and Christ's is God's" (1 Co 3:21-23)... The Office of the Ministry is therefore not to be regarded as a private privilege, which alone belongs to the minister of the Gospel, but is a common privilege belonging to all the members of the Church... [From further lengthy proofs from scripture], it is apparent that every Christian not only has the office of the ministry, but that he also, if he at all wishes to be a Christian, must perform its duties, so that he also confesses the Word, teaches, admonishes, confesses, reproves, and in every way has a care for his neighbor's salvation; that is, for his conversion as well as his preservation in the faith....

But the Lord sees, secondly, how Christians are beset by the frailties of flesh and blood, and on account of this frailty and weakness of the average Christian, God has instituted a special Office of the Ministry of the Word. According to God's Word, certain persons who are prepared, gifted, equipped and tried for this office should be elected, called and set aside from the Christians in general, to perform these offices publicly among them, and in their name thus preach the Word and administer the Sacraments, lead their meeting for mutual edification through God's Word, and are, in fine, the mouth of the Christians.

Wherever the holy apostles established Christian congregations, they, at their departure, did not entrust the office of mutual edification to the converted congregations, so that anyone could publicly teach and lead the others, but they placed certain persons, called elders or bishops, as leaders or overseers. Paul says to his companion and co-worker Titus: "For this cause left I thee in Crete, that thou shouldst set in order the things that are wanting, and ordain elders in every city, as I had appointed thee. If any be blameless... for a bishop must be blameless, as a steward of God... holding fast to the faithful words as he has bee taught" (Ti. 1:5-11). These elders or bishops did not only have the call, like other Christians, to use God's Word over against their neighbors as spiritual priests, but they had definite congregations, whose spiritual service was entrusted to them alone. Peter therefore writes: "the elders which are among you I exhort, who am also an elder... Feed the flock of God which is among you" (1 Pe. 5:1,2). This is not only a good human ordinance, but it is an ordinance instituted by God Himself... [After much explanation from Scripture, concludes], the Public Ministry is therefore a gracious institution of the merciful God, whereby God's Word can henceforth be richly and purely preached and false prophets be warded off, and the Sacraments be properly administered. Thus God's whole dispensation, whether in the Church or the local congregation, is carried out in a good, blessed, and God-pleasing manner.

Although all believing Christians in virtue of their faith have the office of priests, yet they should not perform those duties in such a way that they disturb or abolish the divinely instituted public ministry of the Word in their local congregation. As urgently as the Bible exhorts Christians to be faithful and zealous in the fulfillment of their duties, it nevertheless says: "My brethren, be not many masters" (Ja. 3:1), and Paul, after saying, "God hath set some in the church, first apostles, etc.," asks: "Are all apostles? are all prophets? are all teachers? are all workers of miracles?" (1 Co. 12:28-29). [After further adducing Scripture concludes,] In public assemblies arranged for edification, the lay Christians should not teach, admonish, console, correct, lead in prayer or publicly administer the Sacraments of Baptism or the Lord's Supper, as these are functions reserved for the Christians properly called and ordained by God for this purpose.

But, thirdly, necessity knows no law. In case of need, as,for instance, if the Christians have no publicly appointed pastor, or if he be a false prophet, or if he serves them so seldom that they are in danger of spiritual starvation in case nothing more were done among them, then it is not wrong if also laymen in such cases of need preach the Word and pray in public assemblies or publicly administer Baptism... But they do not function according to the ordinance of God, but as emergency pastors lest needy souls be lost. The Lutheran Symbols, therefore say: Just as in a case of necessity even a layman absolves, and becomes a minister and pastor of another; as Augustine narrates the story of two Christians in a ship, one of whom baptized the catechumen, who after baptism then absolved the baptizer." (TR:67) 9

- God has instituted the office of the public ministry for the public edification of Christians to salvation through God's Word. Unanimously accepted.

- For the public edification of Christians, God has not instituted any other order which should be placed by the side of this. Unanimously accepted.

- When one undertakes to lead the public edification of Christians by the Word, he undertakes and exercises the office of the public ministry. Unanimously accepted.

- It is sin when anyone without call or in the absence of need undertakes this. Unanimously accepted.

- It is both a right and a duty in case of real need for anyone who can to exercise in proper Christian order the office of the public ministry. Unanimously accepted.

- The only correct conception of need is that actual need exists, either where there is no pastor or one cannot be gotten; or if there is a pastor who does not rightly serve them, but teaches falsely; or who cannot serve them sufficiently, but so insufficiently that they cannot be brought to faith or be preserved in faith and guarded against error, and that Christians would succumb from lack of oversight. Two voted against.

- When such need is at hand, it ought to be relieved by a definite and proper order, according to the circumstances. Unanimously accepted. 10

WELS has publicly made plain in their discussions with Missouri on the subject, that we hold to Walther's teaching on Public Ministry. The above is the teaching of Walther, as plainly and simply stated as this author has ever read it. Notice that "the public ministry" described above is one ministry that includes "teaching, admonishing, consoling, correcting, leading in prayer, and public administration of the Sacraments" in public assemblies within the congregation, and is understood as synonymous with the Office of the pastor. Is this the teaching we observe practiced in our WELS congregations? Do laymen publicly teach, preach, and offer prayers in our churches, or Publicly execute other functions of this Office? If it is claimed that such laymen possess a Divine Call, then what constitutes a valid Call and how is possession of a valid Call communicated to the assembly? For that matter, what constitutes valid Approval criteria -- are such criteria arbitrary? And of course, we must ask this with respect to the Office of the Ministry itself, asking what it is? Do we agree with Walther, or not?

---------------------------------------

Endnotes

- Petterson, W. (1926). The Light in the Prison Window: Life and Work of H. N. Hauge. (2nd ed.).Minneapolis: The Christian Literature Company. pp. 73, 173-179.

- Ylvisaker, S (Ed.). (1943). Grace for Grace: A Brief History of the Norwegian Synod. Mankato, MN: Lutheran Synod Book Company. pp. 9-15.

- Ibid. pg. 15.

- Ibid. pp. 16-34.

- Rohne, J. M. (1926). Norwegian American Lutheranism up to 1872. New York: Macmillan. pg. 144-145.

- Ibid. pp. 162-163.

- Ibid. pg. 168.

- Ibid. pg. 168.

- Ibid. pp. 174-178.

- Ibid. pg. 178.