Pietism was a raging problem among Lutherans in mid-19th Century America. It was a movement begun in mid-17th Century Germany by Lutheran theologian Philipp Jakob Spener (d. 1705), with the 1675 publication of Johann Arndt's postils containing a preface written by Spener entitled Pia Desideria, or "Pious Desires." In this preface, Spener called for six seemingly modest Lutheran reforms that he thought would bring about spiritual renewal among Lutherans, extending Luther's doctrinal Reformation into the life and works of the Church and individual believers:

Pietism was a raging problem among Lutherans in mid-19th Century America. It was a movement begun in mid-17th Century Germany by Lutheran theologian Philipp Jakob Spener (d. 1705), with the 1675 publication of Johann Arndt's postils containing a preface written by Spener entitled Pia Desideria, or "Pious Desires." In this preface, Spener called for six seemingly modest Lutheran reforms that he thought would bring about spiritual renewal among Lutherans, extending Luther's doctrinal Reformation into the life and works of the Church and individual believers:- a greater study of Scripture among Christians, assembled in small groups called "conventicles",

- the practicing of the Universal Priesthood of all Believers through lay participation in congregational ministry,

- encouraging Christians to live out their faith, rather than mere intellectual assent to Biblical teaching,

- a more brotherly treatment of heterodox teachers,

- ministerial training that cultivated personal piety as well as academic prowess, and

- preaching which dwelled on Sanctification1,2

Pietism in Germany

Spener’s Pia Desideria spread like wildfire, spawning the movement known as Pietism, which quickly grew beyond his ability to influence it. Before long, Pietism no longer resembled orthodoxy in the slightest, resulting in increasing criticism from orthodox leaders, particularly from Wittenberg. Unable to cope with their criticism, Spener broke with them to form the University of Halle in 1694, along with August Francke (d. 1727) and others, where he hoped to give some form to Pietism and influence it’s practice in wider Christianity.

What the movement came to represent, however, was the replacement of religious objectivism (the fact that man finds outside of himself in the Gospel and Sacraments the assurance that he is a child of God and heir of eternal salvation) with religious subjectivism (the idea that man finds affirmation of his status before God through the experience of certain emotions, and the ability to display certain works), reducing the objective promises of God's Word to secondary stature, and elevating subjective "conversion experiences" (ictic conversion) and displays of pious works in their place; the rejection of orthodoxy altogether, and its replacement with unionistic theological indifferentism; the denigration of the Means of Grace (God coming to man to give him blessings) to opus operatum, a crutch for the complacent Christian, and replacement of these Means with the fervent prayers of the Christian (man going to God in hope of blessings); and use of the Law to make sweeping accusations against society in order to stir the hearts of Christians and to motivate pious works (Law rather than Gospel motivated works), while use of the Gospel was made to raise questions regarding whether one could really lay claim to a living faith (Gospel used as Law).3

What the movement came to represent, however, was the replacement of religious objectivism (the fact that man finds outside of himself in the Gospel and Sacraments the assurance that he is a child of God and heir of eternal salvation) with religious subjectivism (the idea that man finds affirmation of his status before God through the experience of certain emotions, and the ability to display certain works), reducing the objective promises of God's Word to secondary stature, and elevating subjective "conversion experiences" (ictic conversion) and displays of pious works in their place; the rejection of orthodoxy altogether, and its replacement with unionistic theological indifferentism; the denigration of the Means of Grace (God coming to man to give him blessings) to opus operatum, a crutch for the complacent Christian, and replacement of these Means with the fervent prayers of the Christian (man going to God in hope of blessings); and use of the Law to make sweeping accusations against society in order to stir the hearts of Christians and to motivate pious works (Law rather than Gospel motivated works), while use of the Gospel was made to raise questions regarding whether one could really lay claim to a living faith (Gospel used as Law).3Professor John Brenner of Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary, in a lecture entitled The Spirit of Pietism,4 characterized the most potent and critical influences of Pietism in the following way:

- Pietism’s emphasis on Sanctification over Justification resulted in Legalism, by shifting the emphasis in the use of Law from the Second Use (as a mirror) to the Third Use (as a guide) and by prescribing laws of behavior in areas of Christian freedom, leading further to Perfectionism; and

- Pietism’s elevation of religious subjectivism, in addition to what has already been mentioned, also “separated God’s Word from the working of the Holy Spirit” (breaking down the Biblical teaching of the Means of Grace), “changed the Marks of the Church from ‘the gospel rightly proclaimed and the sacrament rightly administered’ to ‘where people are living correctly,’” and “divided the church into groups according to subjective standards of outward behavior.”

- indifferentism, contempt for the Means of Grace, the invalidation of the ministry, the confusing of righteousness by faith with works, millennialism, precisionism, mysticism, the abolition of the spiritual supports, crypto-enthusiasm, reformatism, and making divisions...5

The first wave of Pietism eviscerated orthodox Lutheranism in continental Europe, leaving Christianity unprepared for the next spiritual scourge. Because Pietism viewed the role of intellect in spiritual matters with suspicion and displayed strong preference for emotion and intuition, the Church largely became an unwelcome place for the intellectually capable. So, instead of applying their gifts in service toward God in the Church, such individuals learned to ignore the Church and sought instead to apply their gifts in the realm of secular academia. And so the Enlightenment was born. From the death of Loescher forward, the voice of Lutheran orthodoxy in Germany was rendered silent. The dwindling remnant persevered through remaining pietistic influence and Enlightenment rationalism, until, finally, the Prussian Union -- forced ecumenical mergers between Reformed and Lutheran churches -- rousted what was left of the old, orthodox Lutherans out of Germany. Many of those coming to America landed mostly in Perry County, Missouri and Buffalo, New York.

The first wave of Pietism eviscerated orthodox Lutheranism in continental Europe, leaving Christianity unprepared for the next spiritual scourge. Because Pietism viewed the role of intellect in spiritual matters with suspicion and displayed strong preference for emotion and intuition, the Church largely became an unwelcome place for the intellectually capable. So, instead of applying their gifts in service toward God in the Church, such individuals learned to ignore the Church and sought instead to apply their gifts in the realm of secular academia. And so the Enlightenment was born. From the death of Loescher forward, the voice of Lutheran orthodoxy in Germany was rendered silent. The dwindling remnant persevered through remaining pietistic influence and Enlightenment rationalism, until, finally, the Prussian Union -- forced ecumenical mergers between Reformed and Lutheran churches -- rousted what was left of the old, orthodox Lutherans out of Germany. Many of those coming to America landed mostly in Perry County, Missouri and Buffalo, New York.Ecclesiolae in ecclesia

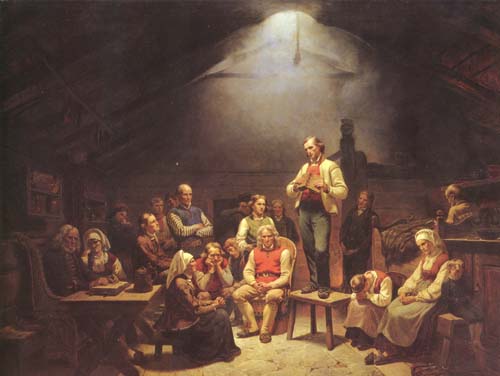

Throughout the period of German Pietism (~1675-1749), some European governments, acting under the advice of the State churches being decimated by Pietism, sought to restore order by passing anti-conventicle laws, as these conventicles had been identified as the hallmark of pietistic activity. Conventicles, under the encouragement of Spener, Francke, and other pietists, were gatherings of Christians within the congregation, sometimes with, most often without pastoral oversight, where individuals were encouraged to study the Scriptures together, express their own thoughts concerning the meaning of a given text, while taking the expression of others within the group as spiritually edifying. As happens in any assembly of humans, an authority structure naturally developed within these conventicles, a structure that was largely dependent upon displays of external piety among the members, in word and/or deed. Such activity elevated the role of the Universal Priesthood of all Believers, as Spener intended, while subverting the authority of the Office of the Holy Ministry, perhaps not as Spener intended. Nevertheless, conventicles became the seat of division and source of false teaching in the Church, and became known as ecclesiolae in ecclesia, or "little churches within the church." Such were disorderly and contrary to the Doctrine of the Call since ministerial authority within the congregation was established outside the appointed order by which individuals were Called to fill the needs of such an Office. In addition, contrary to the Doctrine of the Church, conventicles established "little churches" within the congregation, not only with lay leaders carrying out the roles of the Public Ministry, but often with the inclusion of individuals outside of the congregation and/or outside the Lutheran Confession. As such, small groups were the source of separatism within congregations and from the church body they were part of: the "little churches," without the Marks, without legitimate exercise of the Divine Call, without a Confession and a basis for true biblical Fellowship, became the essence of church life for their members.

The State also had political interest in controlling or eliminating these conventicles, as a result of another peculiarity of Pietism taught by Spener -- a form of millennialism in which the Christian is to hopefully wait for the "better times" of the one-thousand-year reign of Christ on Earth, with a perfect earthly Church being his seat of government.6 This teaching was known to cause various groups to take it upon themselves to work toward such "better times" rather than wait for them, creating political unrest by considering themselves above both the State and the imperfect visible Church, in some places reminiscent of Thomas Muentzer's peasant uprising.7 In other words, conventicles also became hotbeds of subversive political activity.

Haugean Pietism in Norway

In Norway, such a Conventicle Act was passed in 1741. Under the reign of the pietistic state of Denmark, this Act was intended to institute a healthy Pietism in all of its lands, while avoiding its excesses. Its chief purpose was twofold: "To protect those who evinced true solicitude of the edification of themselves and others from persecution, and secondly, to prevent the disorder arising from those who under the cloak of greater religiousness left their natural calling and wandered about from place to place as preachers without having either a divine or human call to do so."8 The specific provisions of this Act are an interesting commentary on what was regarded as problematic with conventicles and lay leadership, even among the moderating pietistic Danes.

According to popular accounts, this Act did very little to promote Pietism at all, however. It is reported that by the close of the 18th Century, the laity had grown entirely complacent and the clergy was increasingly accused of various forms of corruption, not due to a line of corrupt leadership, but through a state-church system that nurtured an unhealthy political separation of clergy from laity.9 Enter the layman, Hans Nielsen Hauge (d. 1824). Raised a farmer, his upbringing consisted in regular reading of Scripture and devotional works (including those of Johann Arndt), the singing and memorization of Lutheran hymnody, and other generally healthy Christian practices. His family being regular church-goers, his upbringing taught him to take his faith seriously, so much so that he was considered odd by his friends and acquaintances, and was a regular object of their ridicule. He was granted perseverance in his faith. At the age of 25, in 1796, singing a hymn while working his father's fields, he was overwhelmed by spiritual experience, prompting him to pray, "Lord, what wilt thou that I should do," whereupon he was reminded of the prophet's words, "Here am I, Lord. Send me."10 And so he went, to the people of his own nation, in whom he saw so much vice and need for faith and repentance, as a lay evangelist intent upon preaching the Way of Salvation through "repentance and conversion," and to do so reverently as a servant of the Church. Yet, Hauge had no Call to preach. At first, he did so haltingly with reticence, but as time progressed and he discovered the approval of those who heard him, as he saw them repent of their sin and embrace their Saviour, he grew more bold and confident. He wrote many devotional books, preached both publicly and privately on many occasions, traveling from one end of Norway to the other in the process. He was a national sensation. One could say that many good things resulted. Many people were turned to Christ. Hauge, being a very bright man, keen on recent developments in farming and gifted with business acumen, also freely assisted his countrymen in their temporal needs, publishing books and offering business and farming advice, even taking part in the creation of several industries. Many people were lifted out of poverty as a result. Yet, having no regular Call to do so, he continued to carry out the functions of the Pastoral Office. Moreover, he abandonded his own Vocational calling to do so. The Church took notice. So did the State. Hauge, despite all the good it may be said that he had done and was doing, did not have in his possession a Divine Call to carry out the functions of the Pastoral Office. He was in violation of the Conventicle Act of 1741, and he was in violation of Scripture, both of which required such a Call.

In 1804, with several short incarcerations already behind him, Hauge was arrested for a tenth, and final time. For ten years he remained in prison, not receiving a finding from the court-commission until 1808, which found him guilty of the following crimes:

In 1804, with several short incarcerations already behind him, Hauge was arrested for a tenth, and final time. For ten years he remained in prison, not receiving a finding from the court-commission until 1808, which found him guilty of the following crimes:- He had violated the Conventicle Act of 1741;

- He had tried to form a sect and a communistic society;

- He had encouraged especially the young people to break the Conventicle Act;

- He had in his writings heaped contempt on the official ministry11

Lay Ministry a Cultural Fixture in Norway, Emigrates to America

During his time in prison, other lay preachers followed in Hauge's footsteps. Young pastors in the Church of Norway adopted his practical and relevant sanctification emphasis and common manner of speaking. Coincident with the growth of Haugean Pietism in Norway, between 1796 and 1814, was a growing political predisposition toward independence. These factors coalesced with the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, resulting in political crisis in Denmark-Norway, which had allied itself with France. Delegates from across Norway were selected from the State Church (in which Hauge and his followers had been active for nearly two decades), as representatives to Norway's Constitutional Convention, which resulted in a new Constitution in May of 1814, emancipating them from Denmark. The followers of Hauge, farmers and other common folk, soon realized "the power that was given them in the Constitution of 1814."14 As they swiftly gained positions of influence in the Church and State, the Conventicle Act of 1741, long ignored since 1814, was officially repealed in 1842, consistent with movements within the government and cultural religious sentiment, driving the nation toward greater liberty.

Hans Nielsen Hauge married for the first time in 1815, lost his wife that same year as she bore him a son, was remarried in 1817, and himself died in 1824. By then, he had become a folk hero, the legacy of Pietism continuing in Norwegian religious culture as a result of his influence. Politically and culturally, religious liberty became synonymous with lay participation in the functions of the Office of the Ministry within the congregation, such that, by the time of the first wave of Norwegian emigration to the United States in the middle of the 19th Century, not only was the practice of laymen carrying out the functions of the Pastoral Office culturally accepted, it was considered a political right. It was also a theological problem, which vexed the young "Old" Norwegian Synod in America for years. How the "old orthodox Lutherans" assisted them in resolving this issue will be the topic of tomorrow's essay (C.F.W. Walther on the Layman's Role in the Congregation's Ministry).

---------------------------------------

Endnotes

- Spener, P. (2002). Pia Desideria. (T. Tappert, Trans.). Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers. (Translation originally published 1964, by Augsburg Fortress. Original work published 1675.). pp. 87-122.

- Schmid, H. (2007). The History of Pietism. (J. Langebartels, Trans.). Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. (Original work published 1863). pp. 38-51.

- Wendland, E. (1991). Present-day pietism. In L. Lange (Ed.) Our Great Heritage (pp. 168-183). Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. pp. 168-183.

- Brenner, J. (2006, October). The Spirit of Pietism. In Rev. Thompson (Chair), Confessional Christian Worldview Conference. Golden Valley, MN.

- Loescher, V. (1998). The Complete Timotheus Verinus (J. Langebartels & R. Koester, Trans.). Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. (Original work published 1718 [Part 1] and 1721 [Part 2]). pg. 249.

- Schmid, H. (2007). The History of Pietism. (J. Langebartels, Trans.). Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. (Original work published 1863). pp. 169-174.

- Loescher, V. (1998). The Complete Timotheus Verinus (J. Langebartels & R. Koester, Trans.). Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House. (Original work published 1718 [Part 1] and 1721 [Part 2]). pp. 36-42.

- Petterson, W. (1926). The Light in the Prison Window: Life and Work of H. N. Hauge. (2nd ed.).Minneapolis: The Christian Literature Company. pp. 18-19.

- ibid. pp. 20-26.

- ibid. pp. 47-48.

- ibid. pp. 165-166.

- ibid. pg. 167.

- ibid. pg. 167.

- ibid. pg. 173.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments will be accepted or rejected based on the sound Christian judgment of the moderators.

Since anonymous comments are not allowed on this blog, please sign your full name at the bottom of every comment, unless it already appears in your identity profile.