Polemics and PedagogicsAs I’m sure our readers have noticed, the position on which we publicly stand, and the nature of raising critical issues of doctrine and practice in a way that can’t help but warn of eroding integrity in our Synod’s claims of unity and in its confessional character,

require us to be not only pedagogical – and even pedantic at times – it also requires us to wax

polemical on occasion. Polemics is an art. It is a use of language that is intended to jar the reader, even upset the reader, for the purpose of pointing out the serious and critical nature of the issue being raised. It is the equivalent of grabbing one by the lapels and shouting at them, not out of anger but out of love and concern for the individual one is communicating with, and out of deep love for and dedication to the Truth. This concern for the Truth and the ultimate welfare of the individual far,

far, overshadows any concern one may have for their immediate feelings, whether they may

feel as if that one is doing the loving thing at the moment or not. In choosing to use polemic as we have, we are convinced that we

are doing the loving thing, regardless of how others may

feel about it (and for most of us, it was this same type of ‘jarring’ that woke us up to reality). We fully realize that the winds of popular opinion blow contrary the use of polemics. Nevertheless, we

have decided that polemics – balanced by pedagogical presentation of the issues – is the proper, confessional use of language that we should make, given the situation(s) we are facing. We will continue to express ourselves in this way, until we are convinced that matters have improved, or that there is sufficient mutual concern across our Synod to suggest that further “shaking by the lapels” is not necessary. In this regard, we take our cue from our Lutheran predecessors in whom the spirit of confessionalism burned white-hot, from the likes of Walther, Pieper, Chemnitz, Luther, and even the soft-hearted Melanchthon – if one considers his polemic against the silly Roman "asses" who neither knew the etymology of the term ‘liturgy,’ nor knew any grammar (

AP XXIV:78-88).

There are a couple things that the concerned reader should know about us, however.

First, most, if not all of us, have been fighting these kinds of battles, or personally working through these issues, for well over a decade. As a former pop-church Evangelical, I myself know the errors of Church Growth from the inside out, having at one time been a fully committed Evangelical, having thought their thoughts, spoken their words, and believed their ‘doctrine’. Once I began to question Church Growth (along with

many other Evangelicals who are

very critical of it), and began to see that its foundation lies in anthropocentric institutionalism, I was led to contemplate the theology that permitted this ideology to have such a gripping authority in today’s pop-church. Deep consideration of these issues is what brought me to the only theological system which successfully avoids man’s participation in God’s work, which is founded on the teaching of the apostles, and which, through its catholic practice, demonstrates unity with true believers spanning all times and places: confessional Lutheranism. When I joined the WELS many years ago, my wife and I, with the encouragement of the orthodox and confessional Lutheran pastor who catechized us, and on the basis of pure scripture doctrine and the practice which proceeds from it, followed through on our new confession, visiting with our friends and our families, and confronting the ministries with which we had long associated, and where necessary (which, in most cases, it was), declaring separation from them.

In a sense, one can sympathize with the Reformed Evangelicals, whether of Calvinist or Arminian stripe, given that they have very little theological framework which would protect them from the allure of Church Growth theories. Confessional Lutherans, on the other hand, have no excuse whatsoever. The only way these ideas can be accommodated by Lutherans is if they discard or relax their commitment to some portion of their rigorous, full and orthodox theology, particularly that of the Means of Grace, the Marks of the Church, and of the Holy Ministry – not to mention Church Fellowship. That Church Growth

has been accommodated by confessional Lutherans, and that

propaganda continues to be issued in favor of it,

is a matter of grave concern. We know it. We see the issues quite clearly. And given our experience with these false ideologies, there is little in terms of substantive argumentation Church Growth advocates can throw at us that we haven’t already fully considered and rehearsed, that we haven’t discussed personally and

ad nauseum with fellow WELS Lutherans or with other Christians.

Second,

Intrepid Lutherans is not ‘Church’. We don’t bear the Marks of the Church. We don’t commune one another, neither have we selected from among ourselves a ‘pastor’ or ‘overseer’. IL is strictly a Universal Priesthood endeavor – all five of us are equals. Nearly all of our posts are shared with one another for mutual approval, and in many cases blog articles are edited and/or enhanced by any number of us before they are published – even though a single author’s name may appear on them. Even some of our blog comments are shared among us for approval before posting.

We stand together. And we’re prepared to fall together. Because of this, we regard any criticism of one of us to be criticism of all of us – which is fine if/when criticism is thought due. We don’t mind criticism (although we may grow weary of it from time to time...), nor would we discourage anyone from criticizing us. Specifically, we encourage those who are critical of us to have the courage to expose their criticisms to public review – to engage us publicly, even as we stand and speak publicly. If someone has a criticism of our public words and actions, then as Paul before Peter and the Elders, “withstand us to the face.” We’ll be happy to meet the challenge.

The other side of this is how we are wont to regard private criticism. It is a forgone conclusion that the loving, biblical and confessional response to ‘public error’ is ‘public rebuke’. We are on public record on this point, having developed a scriptural and confessional foundation for addressing public error in the blog post,

The devil can quote Matthew 18, too – and we will have more to say on this point in the near future. Since our words and actions are public, we therefore

expect to be engaged publicly if one considers them to be in error. Yet, some insist on privately contacting us to offer their criticism. Okay, fine. We’ll take that at face value and respond briefly to their concerns, encouraging them to express further concerns in the public forum provided for them. Usually this is enough. But we’ve been doing this awhile. Wolves have encircled us more than once. Singling out one or the other of us is a tactic used to ‘separate prey from the herd’, to make him vulnerable to attack. Either, one who is perceived as weak is singled out as easy prey in an effort to reduce our numbers, or, one who is perceived as leader is singled out as key to toppling IL altogether. This isn’t to imply that we suspect everyone who contacts us privately with concerns,

or anyone for that matter, is intent upon doing this. Rather, it is to impress upon those who

are intent upon shutting down Intrepid Lutherans, that we

will not be separated or dealt with individually and privately for matters relating to words and actions we engage in together and in public. Critics, to be taken seriously, simply need to subject their concerns to the same public critique that we offer ours.

This has already gotten long, but there are a couple of points which come up frequently enough, that would benefit from some mild rebuttal. Those points concern the ‘tone’ of posts and commentary, and with identifying ‘motivations’ of those who express themselves publicly.

Obsession with ‘tone’ and ‘motivations’ is a characteristic of postmodernismIn the past several months, some have quite genuinely presented to us their concerns over ‘tone’ in some of the posts and commentary on our blog. Generally, our practice is to allow signed comments, which express complete thoughts in relation to the blog post or immediate commentary, even if one can find fault with the ‘tone.’ This practice is subject, of course, to our own sanctified judgment, as we clearly state in our

“Rules of Engagement” guidelines. We realize that this automatically places this blog outside the comfort zone of those who prefer that public discourse among Christians be slathered with evangelical slobber. We don’t find that sort of expression to be at all necessary in this forum. Yet even within the guidelines we have published, our judgment is not always perfect, and some comments will be posted that we would normally hold back. Where this may have happened in the past, we trust that this has been the exception rather than the rule, and where individuals have expressed concern regarding ‘tone,’ be assured, we definitely take these concerns to heart, and strive to make changes where we think warranted.

In most cases, however, concerns of this sort are delivered to us in some form of analysis assigning ‘objective value’ to interpretations of ‘tone’, essentially identifying imperative statements as “unloving arrogance.” I’ll admit that grammatical analysis does make a critique of ‘tone’

sound objective, and while the grammar seems to be conclusive, any valuation of ‘tone’ – whether it be good or bad – is ultimately a matter of the reader’s subjective interpretation. It is

not objective. Perceptions of ‘tone’, therefore, are often more of a ‘problem’ with the reader than with the author of such statements. To be sure, this is quite a serious problem. In fact, I would submit that readers or listeners who are so distracted by their own obsession with how they feel about another person’s expression, rather than with the content of that expression itself, are themselves displaying evidence of a self-centered disrespect for the author or speaker. It is sin. And this is not something I’m just making up, or some obscure point that few people have ever considered, but a basic tenet of objective critique that has been recognized for centuries.

Perhaps many readers of IL are too young to know what a

real education is. Maybe, maybe not, I don’t know. But I

do know that if

I have a real education, I received it entirely by accident. By the time I started college, postmodernism was already the dominant worldview among the younger faculty, and the methods of social constructivism had begun to replace the long established classical and even modernist pedagogies. Yet, as an undergraduate and graduate student, I deliberately chose the most difficult and disliked professors I could find – since I was paying for my education, I wanted to get my money’s worth. Most of these professors were the old guys, the one’s who were mid-career already during the tumult of the ‘60s.

They had a

real education, and were doing what they could to pass it along, while all around them real education was disintegrating. What they taught their students about critique was very simple:

one must make every effort to remove himself from the expression of others, and regard that expression only in terms of what the vessel of language – vocabulary and grammar – provides. If someone goes to the effort to give expression to his/her thoughts by composing words within a definite grammatical structure, then the

only basis for properly understanding that expression is to interpret it on the basis of that composition, on the basis of objective rules of expression to which both the reader and the author agree. And this is the

only basis on which one’s expression can be given due respect and consideration.

Postmodernism, as I’m sure the reader well-knows, has turned this completely on its head. According to the postmodernists,

language is insufficient to carry the full meaning of an author’s or speaker’s expression, is

insufficient to communicate any matter of truth with certainty. In order to more fully understand the expression of another person then, postmodernists insist that it must be understood from within the context of that person’s

narrative. Hence today’s overriding obsession with a person’s motivations, and the life experiences that lie behind them, which lead to his manner of expression. These are prerequisite to understanding the content of his expression. But how does the listener or reader understand the narrative of another person? Through language? No – language, again, is insufficient. Rather, language needs to be complemented with other devices of communication. A person’s narrative needs to be received aurally, visually, tactilely – that is,

experientially. Above all, however, it must be received

socially. That is, the narrative of one person must be delivered to another person in the form of experience, and in this way received and incorporated into the narrative of the second person. Thus the two individuals are socially connected by

shared narrative. And this represents the epistemology of postmodernism: knowledge is a social construction that is built as narrative is normalized across a given people group. Because of this, again, according to postmodernism, all ‘truth’ is also tenuous: (a) because social experience changes over time, the knowledge construct, or schemata, of a people group will also change, (b) because knowledge construction differs from one people group to another, and (c) because the means through which knowledge is constructed (i.e., through experience) is ultimately inconclusive with respect to what one may call ‘true’ anyway. Thus, no one could possibly be certain enough about anything to be

imperative about it, and naturally, to be imperative about anything is to be ‘arrogant,’ as it is to regard any position as anything but ‘opinion.’ This is what it means to “understand motivations” in our postmodern age, especially when words are regarded as insufficient to evaluate another person’s expression. But be warned, dear reader, this philosophy is

completely incompatible with the principle of confessionalism, and it is something against which we must struggle if we are to hold on to the Truth.

Apprehension, doubt, and self-censorship: Living under LawFinally, it must be stated that living out one’s life in abject fear of ‘offending’ another person (and by ‘offense’ in this case, let’s be clear – we don’t mean ‘offense’ in the biblical and confessional sense, of violating someone’s conscience or leading them into sin – all that is really meant is ‘hurt feelings’), of being forced by others to constantly predict how a person may subjectively react to one’s own expression, and to censor one’s expression according to these worthless predictions, is

a life under the impossible expectations of the Law. Further, if the expectation is that the expression of one’s conscience be self-censored to avoid the ‘hurt feelings’ of others, this expectation

is itself true ‘offense’ in the biblical and confessional sense, being a violation of one’s conscience which forces one into habitually fraudulent self-representation. One is forced under these circumstances, to cover up what they really think and obscure who they really are in order to please those wagging the billy club of the Law above their heads.

No, it is best to allow and encourage people to honestly express themselves at all times, not to force them to constantly second-guess or question everything they might say for fear of hurting someone else’s feelings, or worse, out of fear that what they are convinced is true may really be error. This is neither the confidence nor the ardor of a confessor. The fact is, if a fellow Christian is guilty of error, it will be immediately evident in his expression and will be far more easily and directly dealt with, if he is expressing himself consistently with his character and convictions, than if he is coerced into hiding them through continually dishonest self-expression. At the same time, people ought to be encouraged to live a life of meditation on the Scriptures, and of self-reflection, so that if, after the fact, one can confess that a better course of action could have been taken, or that his thinking ought to be corrected, then that adjustment can be made voluntarily and permanently on his own.

Dealing with subjective concerns regarding 'tone': a sugggestion and advice for the 'offended'One may complain that they are, nevertheless, subjectively concerned about ‘tone’. It may not sound like it, but I

can appreciate that. My suggestion is this: instead of trying to change people to one’s own liking, one ought to endeavor to train oneself to

objectively critique the expression of others, and to respond to that expression objectively, rather than become emotionally vested in his own subjective evaluations of ‘true intent or meaning’ which are based on his perceptions of ‘tone.’ As stated above, the practice we at Intrepid Lutherans have adopted is to exercise our own collective judgment in those posts we allow to be posted, but to generally allow folks to express their thoughts, even if one can find fault with the ‘tone’ – understanding that as we deal with the content of their expression, the tone will likely change anyway.

In closing, and for what it is worth, I’ll offer some advice in addition to my suggestion, by sharing a practice I try to follow as I take up issues in a public forum. First, remove yourself from your own commentary – that is remove, as much as possible, use of the terms “I” or “me”. While this does not prevent your commentary from being critiqued by others, it does help to keep yourself from becoming a part of their critique. Since you have not made yourself part of the subject of your own commentary, it will be difficult for others to legitimately make you the subject of their response. Second, remove reference to other people from your commentary – that is, remove names of people, as much as possible, and when responding directly to what someone has written on these pages, try to eliminate personal terms like “you” as you address the content of their expression. With these simple guidelines, I have found that, apart from cordial salutations, all that remains is discussion over the ideas at issue, and that it is sufficiently abstracted from myself and from the individuals engaged in the discussion that a direct and spirited exchange regarding the issues can be fruitfully had. One can rail up and down against the positions that others take, and it doesn’t become personal – nor does it need to become personal for the words to be persuasive. Thoughtful and genuine conversants will voluntarily apply the words of such dialogue to themselves as those words seem apt. Of course, it goes without saying, I am imperfect, and fail to take my own advice all too often (as those who know me personally will be quick to point out, I’m afraid!) – but I find that this practice tends, more than anything else, to contribute to civilized debate and is a standard worth pursuing.

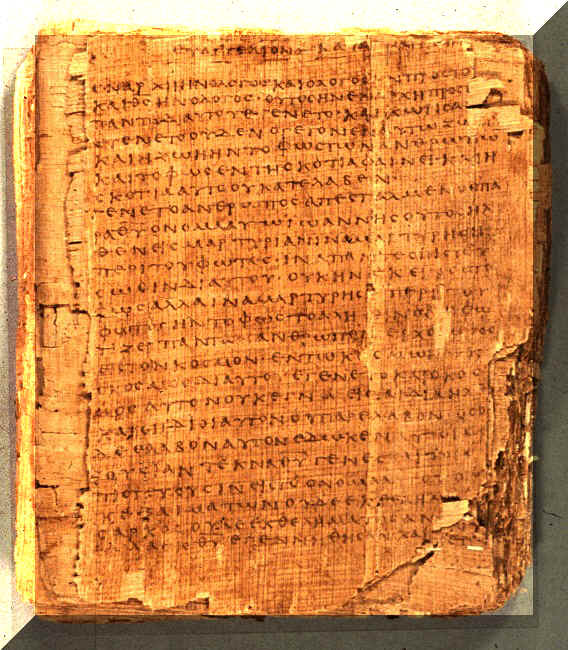

Word is now coming out that a letter has been discovered that was written to St. Paul, in response to his letter to the churches in Galatia. Here is an English translation.

Word is now coming out that a letter has been discovered that was written to St. Paul, in response to his letter to the churches in Galatia. Here is an English translation. The foregoing was posted on Rev. Paul T. McCain's blog, Cyberbrethren, last week. When we read it, we thought it appropriate as an object of discussion on our own blog, and sought permission to cross-post his blog entry on Intrepid Lutherans. Of course, this piece is satire. We feel compelled to state as much before the reader comments, given that a number of the Cyberbrethren commenters didn't get it.

The foregoing was posted on Rev. Paul T. McCain's blog, Cyberbrethren, last week. When we read it, we thought it appropriate as an object of discussion on our own blog, and sought permission to cross-post his blog entry on Intrepid Lutherans. Of course, this piece is satire. We feel compelled to state as much before the reader comments, given that a number of the Cyberbrethren commenters didn't get it.