It is a simple and inconsequential matter to engage in discourse when parties to the discussion agree beforehand that the matters at hand are merely “opinions.” Indeed, often a ridiculous game of charades is played, seemingly by double jointed circus acrobats, no-less, to either reduce matters of genuine consequence to inconsequential matters of “opinion,” or to at least agree to treat them as such throughout discussion. People are allowed to differ on matters of opinion. They can come to the discussion table with their opinions, and leave the table afterward still clinging to them. This is because all opinions are equal – equally invalid and equally inconsequential. But the moment matters are recognized as more than this, the moment it is realized that there may well be a correct party and an incorrect party who come to the table for discussion, tolerance for good-faith discourse plummets. To differ in matters of consequence can only lead to a compulsory change in thinking or to separation. Pride will not allow the indignity of being wrong, especially when being wrong means the wrong party must change or be blamed for the resulting separation. Thus, meaningless discussion is far more preferable to those who are intolerant and prideful.

“Agreement” in our post-Modern Era: Argumentation or Negotiation?

And, of course, the prevailing winds of post-Modern culture play right into the weaknesses of human pride. These days, the greatest sin against one's fellow man is, first, to claim, and even worse, to demonstrate, that he is wrong about something. How arrogant! Post-Modernism teaches that everyone is “correct” from his own point of view – such views being informed by, and, as a pragmatic matter, only extending as far as, one's immediate social context. As a result, it is utterly disrespectful for anyone to tear another away from the security, happiness and social utility of his point of view, especially given that, by definition, neither his point of view, nor anyone else's, is, or can be, one that is “correct” or “true” from any transcendent or objective standpoint. Unless a matter is one of absolute or objective truth, it is not worth arguing about; and since post-Modernism cannot allow any such thing as a truth which transcends one's immediate social and linguistic construct, there is no truth having any aspect which qualifies as worthy of argument at all. Hence, to do so anyway, for any reason, is by definition utterly offensive, one of the worst social sins a person can commit against another.

So how can two parties possibly come to agreement, when agreement of some sort is necessary for at least practical reasons? Consulting any basic Communications Theory textbook will provide the answer. There are two methods via which opposing parties may come to agreement. The first is argument. When parties to such a discussion “make their argument,” their objective is to persuade members of opposing parties to their position through honest debate. Thus, the agreement that is sought via the method of argument is “agreement in principle.” There are really no advocates for this method anymore, though it still gets brief treatment in the textbooks. Post-Modernism has succeeded in eliminating argument as a relevant method for arriving at agreement, since it has reduced the idea of truth to a self-referential socio-linguistic construction of no more substantive content than what is dictated by the pragmatic social need requiring its justification. In other words, post-Modernism tells us that there are no issues requiring “agreement in principle” since no such issues can be defined – all matters of so-called “Truth,” or Conscience, are nothing more than expedients, and expedients are not worth arguing over, certainly not worth the trouble of disrupting existing “political harmony.” Thus, argument is just an artifact of the West’s unenlightened past, deserving honorable mention and brief description in the textbooks due to it’s recent and prominent role in Western Society, but otherwise deserving little emphasis.

The method of securing agreement between parties which most textbooks give great attention to is also the method which is most widely used, the method which most respects the opinions of the parties involved by allowing them to retain their perspectives after the process has concluded. This second method is negotiation. When negotiating parties meet, they have no interest in principle. They are immediately prepared to compromise, as this method requires them, while they seek to induce opposing parties into greater compromise – which is the “victory” offered by negotiation. Knowing this, parties involved in negotiation initially come to the table deliberately misrepresenting themselves, expending great effort to defend far more than their genuine interests, in order that they may more easily compromise the views they publicly represent to satisfy opposing parties. Thus the method of negotiation, unlike the method of argument which requires honest debate from its participants, is not an honest method at all, but is fundamentally dishonest. When all parties are satisfied, the “agreement” reached by them is merely that – a satisfaction with the mutual compromises opposing parties express a willingness to live with. But such “agreement” never lasts, as “satisfaction” and “willingness” are subjective and fickle criteria; and such “agreement” never results in genuine peace, as the negotiating parties depart with the same fundamental disagreements that brought them together in the first place. At the conclusion of the process of negotiation, all parties know that they will meet again in the future, to seek further compromise from their opponents.

Confessional Christianity is founded on and requires Argumentation as a method of resolving differences

The matters at issue in the method of argument are the matters to be resolved and agreed upon in principle. The matters at issue in the method of negotiation are inconsequential matters to be compromised – they are expedients to be disposed of for other purposes. Yet, negotiation and compromise seem to be the first words mentioned when “peace” is desired. What a pity that matters of Conscience can be reduced to matters of opinion, used as political or financial leverage, or defiled as some other form of expedient; but such is, and has been, the treatment Scripture Teaching and Christian Conscience has seen throughout the ugly past of the visible Church’s political history. Luther himself warned of “compromise,” being credited with the saying, “Compromise never leads to peace, it only postpones conflict.” Indeed, the April 2011 essay published on Intrepid Lutherans entitled Differences between Reformed and Lutheran Doctrines recounts one of Luther’s experiences with compromisers in the Church:

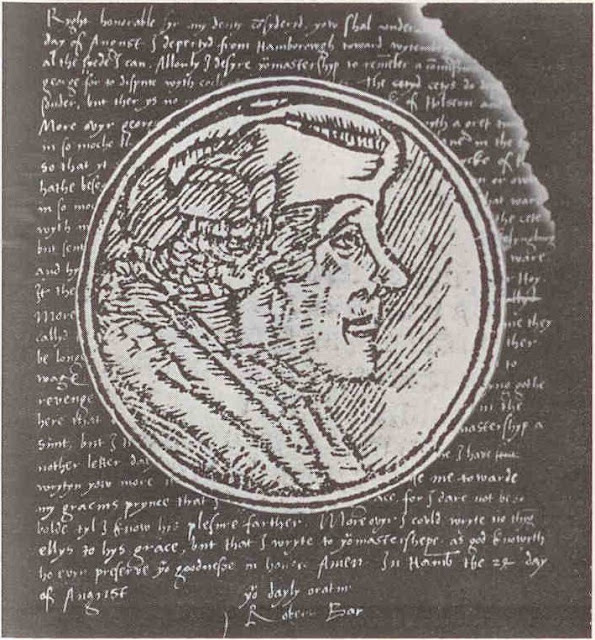

- ...even though they approached the Scriptures from essentially incompatible starting points, Zwingli and Luther found themselves in such agreement that they desired to meet, to debate those points of disagreement in hopes of resolving them and of declaring their unity under the teachings of Scripture. They met in 1529. The event is known as the Colloquy of Marburg. With fifteen critical points of doctrine separating them when they met, after their debate the separation was reduced to only one, that of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist – Zwingli and his followers having conceded every other point of doctrine to Dr. Luther. On this final point, Luther opened the discussion by drawing a large circle on a table and within it writing the words “This is my body.” Zwingli objected to the plain meaning of the words offered in Scripture on the basis that “the physical and the spiritual are incompatible,” and that therefore the presence of Christ can only be spiritual. He insisted that the words must be symbolic, and no more. Despite their fundamental disagreement, however, Zwingli conceded to the same use of language as the Germans under Luther, if only between them they understood that while Luther meant that Christ was both physically and spiritually present, Zwingli meant that He was only spiritually present. At this, Dr. Luther became incredulous. It was one thing to misunderstand Scripture – to be a weak and erring brother – but it was quite another to knowingly allow a misrepresentation of Scripture to stand for the sake of outward unity. The result is not Scriptural unity – full agreement regarding what the Scriptures teach. On the contrary, such a compromise would result in a purely outward, political unity. That Zwingli was willing to compromise regarding what he was convinced, as a matter conscience, the Scriptures taught, signaled to Dr. Luther that all of his concessions at Marburg were just that – compromises. Thus Dr. Luther pronounced to Zwingli, “Yours is of a different spirit than ours,” cutting Zwingli to the bone, and ending the Colloquy. Six months later, Dr. Luther was proven correct: Zwingli reversed all of the concessions he made at Marburg, announcing that he never really agreed to them in the first place.

The process is simple. First, have the courage to identify issues divisive of unity; second, have the courage to publicly admit that they are divisive of unity; third, publicly debate those issues with the purpose of persuading opponents, while being open to being persuaded; fourth, resolve the issue with genuine agreement, or, have the courage to admit that agreement has not been reached and that separation must occur. In either case, whether unity or separation results, peace prevails for all parties who no longer have to suffer under disagreement in matters of Conscience.

A World at War... united against Christ's Church

Yet our post-Modern culture militates against the methods of argument that are so needed by the Church. Today, so-called “Conscience” and the Confession which follows from it is nothing more than “socially informed opinion,” a disposable thing of no consequence to anyone, either specifically or generally. It is certainly nothing which merits recognition by the State anymore, much less legislative or executive consideration. And it's a foregone conclusion that matters of principle are nothing to wage war over anymore, either – the only national interests that seem to be justifiable are pragmatic concerns ultimately impacting a nation's ability to remain profitable. Sadly, such hopelessly self-referential thought patterns of post-Modern Western Culture now dominate the minds of average Christians, too, eroding any semblance of a distinctly Christian, much less Lutheran, Worldview, especially among those who are addicted to mass media entertainments which serve as the prime conduits through which these worldly philosophies are being disseminated and reinforced.

The World is not a friend of Christ’s Church. It is her sworn, mortal enemy. We at Intrepid Lutherans touch upon this frequently, but most directly in our series "Relevance," and Mockery of the Holy Martyrs. Those who are consumed with the World’s thinking bring that thinking into the Church, to defile its most precious possession, the pure teachings of Christ preserved for us in His Word, as expedients for Wordly and temporal purposes.