[The following is a response to

a commenter who asked regarding the differences between Reformed and Lutheran theology. The following response was a little too long to post as a comment...]

Patricia,

I realize this response is a little late in coming, but I have finally found the time that I earlier thought I would have had, to work up a brief response to your questions on “differences” between “Reformed” and “Lutheran” teachings. The difficulty in making such a comparison, of course, is in first defining what we mean by “Reformed” – and also what we mean by “Lutheran” – systems of theology. What

we mean by the “Lutheran system of theology,” firstly, is what we publicly

confess, in the

Lutheran Book of Concord of 1580 (which contains the

confessional documents of Lutheranism, such as the

Augsburg Confession and the

Formula of Concord), to be the teaching of Scripture on points which are generally disputed by Christians; secondly, is that body of theological writings which have come to us since the Reformation, and which in many cases existed even long prior to it, that are faithful to the very words of Scripture as well as these confessional documents. This is what we mean, therefore, when we qualify ourselves as

confessional Lutherans, as those who subscribe to and meticulously affirm the teachings of Scripture as expressed in the Book of Concord. This subscription implies a relatively reliable consistency throughout the history of confessional Lutheranism, making it reasonable to characterize what “we” believe, teach and confess. It is also the reason why, though you asked me what “I” believe, I can answer you by describing what “we” believe: all ~400,000 of us in the

Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), and especially the ~1,000 pastors who serve us in various capacities, enjoy a unity of belief, publicly confessing the same doctrine and striving to represent that doctrine in our public practice. That this unity, due to our own fallibility, is imperfect, we all admit – which is why, though we take such confessions at face value, we do not rest secure in them but continually examine and affirm our doctrines according to the teachings of Scripture and the Lutheran Confessions, and evaluate our practices relative to them. This is also why we are diligent to point out to our brothers when we detect that their doctrine or practice may be straying from our mutual confession, in order to call them to repentance (or to have ourselves corrected) that we may continue to enjoy our unity and to work together for the Truth. This latter point, is the primary reason our blog exists.

We also qualify ourselves as

confessional Lutherans to distinguish ourselves from the vast majority of “Lutherans” throughout the world (~65 million) who have been given over to the errors of Liberal protestantism, who have given up the Reformation principle of

Sola Scriptura (“Scripture Alone”), and therefore, in our opinion, even the right to call themselves “Lutheran” at all. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is one such “Lutheran” church body – and believe me, it is no small matter of frustration for us

confessional Lutherans that the ELCA continues to retain the label “Lutheran.” Out of the number of people in the world who allow the label “Lutheran” to apply to themselves, we would estimate that ~5 million could safely be characterized as

confessional, ~3 million of which are located in the USA (and those estimates are probably a bit optimistic). Of those ~5 million, WELS enjoys full agreement in all matters of doctrine and practice with approximately 10 percent, in twenty other church bodies throughout the world, as members of the

Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference (CELC). Outside of that 10%, we stand separate, both in order to preserve true unity among ourselves under God’s Word, and in order to call the others to repentance.

(NOTE: The author, though at the time he wrote this essay was a member of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod [WELS], has since left that church body over serious issues of doctrine and practice, and is now a member of an independant Lutheran congregation, served by a pastor from the Evangelical Lutheran Diocese of North America (ELDoNA). Though none of the issues prompting him to leave the WELS impact the content of this essay, given the frequency with which this essay is visited each week, it may nevertheless be of interest to the reader to know what those issues were. Those issues were explained in a letter to his former congregation that was made public on this blog: What do you do with a Certified Letter? Here is one idea.... If the reader has further interest in the ELDoNA, he may also read the author's nine-part series, published in June and July of 2013, beginning with the post Impressions from My Visit with ELDoNA at their 2013 Colloquium and Synod – PART I.)

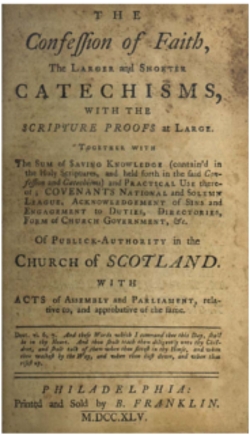

As complex as that may seem, what we would identify as a “Reformed system of theology” is a little more difficult to pin down these days. The Reformed confession with the widest subscription is the

Westminster Confession, although there are quite a number of other historical confessions that are important among the Reformed, including the

Belgic Confession (Dutch Reformed) and the

Gallic Confession, all of which would be strongly identified with the teachings of Calvinism. However, also falling under the umbrella of a “Reformed system of theology” are the teachings of Arminianism, which have influenced many Baptist groups since the 17

th Century, and which characterize the theology of Methodist and Wesleyan traditions. While there are a variety of confessions and “teachings” which would officially fall under the umbrella of a “Reformed system of theology,” there is the added problem that, generally speaking, there does not seem to be firm commitment among those who identify themselves these days as “Reformed” to any specific confession or body of theology. Although there seems to be a growing confessional movement among some Reformed Calvinists, for the most part, we see Reformed teaching as a continuum between Reformed Calvinism and Reformed Arminianism – and this is especially the case in modern American Evangelicalism, which, due to its inherent ecumenism, tends to broadly yet non-specifically identify with Reformed teaching.

Anyway, I checked out the church body you are a member of – the

Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (ARP) – and according to your

doctrinal statements, your church body confesses the

Westminster Confession, placing you square within a Calvinist confession. The doctrinal statements of our church body, the

Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), can be found online in the document entitled,

This We Believe, which is a document which clearly states, in thesis/anti-thesis format, our position with respect to Christian doctrines that are generally disputed. Another document, entitled,

What the Bible and Lutherans Teach is a positive description of the doctrines that all confessional Lutherans, and many other Christians, agree on. Unfortunately, neither of these documents appear to be available from the WELS website in PDF format anymore, so these web documents will have to suffice for the purposes of comparison with the PDF your church body provides. In addition, Luther’s

Large Catechism and

Small Catechism are contained in the Lutheran Book of Concord, and may make for an interesting comparison with the large and small Westminster Catechism’s, as well.

Given the availability of these documents, what I am

not going to do is walk through them line by line (since I am sure that you are fully capable of doing so). Instead, I will describe in sentence-paragraph format some of the main differences between Reformed (Calvinist) and confessional Lutheran teaching as I have encountered them, starting with a bit of history, and then concluding with recommendations for additional books, if you’re interested in further study.

Some influences on the Swiss and German Reformers, both common and divergentThe foundation for both the agreement and the disagreement we find between Reformed Calvinist and confessional Lutheran bodies of doctrine can be traced to the period of the Reformation itself, generally to the

Renaissance, which carried with it the very positive

humanist priority of

ad fontes, of returning to the

sources of knowledge – like the original texts of the Bible, of the Greek philosophers, of the Roman statesmen, etc. This was a reaction against the method of Mediæval and Scholastic traditions of education, which at that time bound contemporary knowledge to the accumulated wisdom of the ages that was represented, not in the original documents themselves, but in commentaries of the originals, and commentaries on the commentaries, and commentaries on those commentaries, etc., compounded through the centuries. Along with this new-found fidelity to the sources, came a new form of learning which rested on examination and assimilation of those sources.

We also find more specific, and divergent, influences in the social, political and religious realities of the regions where the Swiss and German Reformations took place. While Germany and the Alsace were firmly within the rule of the Holy Roman Empire, France was independent from it, the nobility of France having been established since the time of the Carolingians, and Switzerland was growing in its independence from the Empire, having formed a confederation of independent states, adopted a republican form of government and even graduated by then to a form of democratic-republic. The leaders of the Reformation in Germany were

Dr.’s Martin Luther,

Phillip Melanchthon and (at first)

Andreas Karlstadt. In the generation following Luther,

Dr. Martin Chemnitz led the Lutherans to unity, serving as principle author of the

Formula of Concord, and gathering the other confessional documents into a single collection called the

Book of Concord, to which all Lutherans, in order to be Lutherans, would unconditionally subscribe. In Switzerland, the leaders of the Reformation were

Ulrich Zwingli (German Switzerland), and later,

John Calvin and

Theodore Beza (French Switzerland).

John Knox led the Reformation in Scotland, following from his association with John Calvin.

In Germany, Luther, as an Augustinian monk and professional theologian, wrestled with the reality of his own salvation, struggling under the unbalanced notions of God as a Righteous Lawgiver and angry Judge, who demanded that man follow His Law for the sake of his own salvation. He realized that he, as a depraved sinner, could not keep the Law; but the collected wisdom of the Roman church taught that he

must.

As a professor at the University of Wittenberg, Luther lectured on the books of the New Testament. Influenced by the new Renaissance learning, rather than relying on the old commentaries, Luther prepared for his lectures by meticulously studying the books of the New Testament directly, not only in Latin, but in their original language, as well. There he discovered that indeed, the Law

is harsh and demanding, that man

is depraved and incapable of its demands, but most importantly, that man is Justified, not by the works of the Law, but by faith alone in the promises of Jesus Christ. When he discovered that the Church’s teaching under the Roman Pope was false and damnably misleading, he sought to

reform the Roman Church, to return the Church to the true apostolic doctrine and biblical practice. Thus the German Reformation under Luther was principally about man’s relationship with God (i.e., by God’s grace alone through faith alone in Christ’s redemptive work alone), the importance of pure Scripture doctrine to maintain the correct view of that relationship (Scripture alone), and the subordinate role of human reason to the authority of Scripture. The German Reformation was a

conservative one – one which looked back through the history of the Church to the teaching of the Apostles, seeking to correct only what was in error while

conserving the rest, and maintaining the character, unity and continuity of the Church. The resultant separation from Rome and loss of visible unity was something that was necessary due to Rome’s obstinacy, but which was neither planned nor desired.

Such was not the case in Zurich, however. Ulrich Zwingli, a Roman Catholic priest, had involved himself deeply in the humanist movement and had earned a reputation as an outspoken activist. He was very active in politics, as a proponent of the cause of Swiss unity and independence. This cause faced itself in the direction of the future, not the past, and thus required a new platform for social order. Hence, when he sequestered himself in his house to study the Scriptures, Zwingli’s purpose was

not to reform the Church. The Swiss needed a new one. On the contrary, his purpose was to ‘develop a true philosophy of Christ’ which would ‘impact social and political change.’ Thus the Swiss Reformation, under Zwingli (and later, Calvin and Beza), was not a conservative one, but radical. Without knowing what they may be, one can perhaps already appreciate that such differences of purpose would result in differences of doctrine.

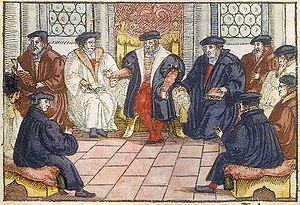

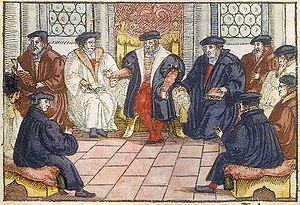

Luther and Zwingli meet to discuss doctrine

Nevertheless, the Renaissance principles of humanist learning at the time – principles shared by

all the reformers – required fidelity to the sources. The result was that, even though they approached the Scriptures from essentially incompatible starting points, Zwingli and Luther found themselves in such agreement that they desired to meet, to debate those points of disagreement in hopes of resolving them and of declaring their unity under the teachings of Scripture. They met in 1529. The event is known as the

Colloquy of Marburg. With fifteen critical points of doctrine separating them when they met, after their debate the separation was reduced to only one, that of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist – Zwingli and his followers having

conceded every other point of doctrine to Dr. Luther. On this final point, Luther opened the discussion by drawing a large circle on a table and within it writing the words “This

is my body.” Zwingli objected to the plain meaning of the words offered in Scripture on the basis that “the physical and the spiritual are incompatible,” and that therefore the presence of Christ can only be spiritual. He insisted that the words must be symbolic, and no more. Despite their fundamental disagreement, however, Zwingli conceded

to the same use of language as the Germans under Luther, if only between them they understood that while Luther meant that Christ was both physically and spiritually present, Zwingli meant that He was only spiritually present. At this, Dr. Luther became incredulous. It was one thing to misunderstand Scripture – to be a weak and erring brother – but it was quite another to knowingly allow a misrepresentation of Scripture to stand for the sake of outward unity. The result is not Scriptural unity – full agreement regarding what the Scriptures teach. On the contrary, such a compromise would result in a purely outward,

political unity. That Zwingli was willing to compromise regarding what he was convinced, as a matter conscience, the Scriptures taught, signaled to Dr. Luther that all of his concessions at Marburg were just that – compromises. Thus Dr. Luther pronounced to Zwingli, “Yours is of a different spirit than ours,” cutting Zwingli to the bone, and ending the Colloquy. Six months later, Dr. Luther was proven correct: Zwingli reversed all of the concessions he made at Marburg, announcing that he never really agreed to them in the first place.

Significant differences between Reformed and Lutheran teaching remainFrom this episode of history, we learn of several differences which impact Reformed and Lutheran teaching to this day, beginning with the role of human reason relative to the Scriptures, and extending to the teachings of Predestination, of Christology, of God’s Grace and the Means through which He works, of Baptism, and of the Lord’s Supper. There are other doctrines impacted, of course, but these will suffice.

They differ regarding the role and authority of human reason with respect to Scripture

Luther and Zwingli, like Calvin and Beza who followed him, were exceptionally well-educated men, learning, teaching and leading during an exciting time of rediscovery, intellectual cultivation and application of the classical sources. The gift of the Renaissance was that men once again learned the art of human reason from the

masters. But if reason were to remain a true gift, and not a Trojan Horse, what authority should it carry in matters of Scripture’s teaching? Luther insisted that human reason must remain subordinate to the very words of Scripture – as “the handmaiden of Scripture.” If seeming paradoxes of Scripture could be harmonized through use of reason, without compromising the plain meaning of the statements of Scripture as one would understood them in their natural context, then such was considered helpful. If, however, such harmonization required that the plain meaning of the Scriptures be understood differently than they directly stated, then the words of Scripture, along with the paradox, stood, while reason was subordinated to them. Zwingli, and later Calvin, thought differently. They reasoned that Scripture, as pure Truth revealed by God, could not contain paradox or mystery. As a result, they required a closed system of theology, against which unsanctified reason was powerless, since all questions were reasonably answered. Thus, in Reformed systems of theology, reason is more than just the “handmaiden” of Scripture, but in many cases, stands as its arbiter.

They differ regarding the starting point of Christian teaching and central teaching of Scripture

One of the first evidences of the difference between Reformed and Lutheran teaching regarding the role and authority of human reason, is in the starting point of their respective systems of theology. John Calvin saw the unfolding of Scripture – the power of God’s Word that by it He could speak the universe into existence, that infractions of His Holy Law would carry eternal consequences, that He accomplished man’s Salvation and is solely responsible for it apart from man’s miserable efforts – as the story of God’s omnipotence. A very reasonable conclusion, indeed. Hence, God’s Sovereignty, according to Calvin, is the subject of Scripture, and is therefore the starting point of the Calvinist system of theology, with the central doctrine being that of Sovereign Grace – that God has mercy on those whom He will, apart from any effort of their own. Lutherans, on the other hand, while not denying the Sovereignty of God in any respect, nor that He alone, apart from man’s efforts, is responsible for man’s salvation, take Scripture’s own testimony regarding its subject: Jesus refers to the Old Testament Scriptures as “they which testify of Me” (

Jn. 5:39), and the New Testament directly testifies the same regarding itself – in other words, according to the direct testimony of the Bible, its subject is the Messiah, Jesus Christ. Thus, the starting point in the Lutheran system of theology is

not God’s Sovereignty, but the person of Jesus Christ, and our central doctrine is Justification by Faith Alone – the teaching by which we gain access to His gracious work on behalf of all mankind (

Ro. 5:1-2).

They differ regarding the person of ChristBut Who is Jesus? We Lutherans, like the Reformed, teach that Jesus is both fully God and fully man. But there the similarity ends, for we Lutherans, confessing with Scripture that, “in Him dwelleth

all the fullness of the Godhead

bodily” (

Co. 2:9), also believe and teach that Jesus in His divine nature shared in His human attributes, and in His human nature shared in His divine attributes. As Luther taught,

Wherever you can say, “There is the Son of Man,” there also you must say, “There is the Son of God.” The Reformed reject the teaching that Jesus in His human nature shared in His divine attributes, that the Son of Man is omniscient (though

Jn. 1:43-51; 11:3-11; Mt. 16:21 show Jesus’ omniscience as man), omnipotent (

Mt. 9:6; 28:18 show Jesus claiming omnipotence to Himself as man) or bodily omnipresent (

Mt. 28:20; Ep. 1:23; 4:10 show Jesus as bodily omnipresent). This may seem like much ado over nothing, until one asks himself the following questions:

Who was it who died on the cross? Surely, Jesus in His human nature died on the cross, but did Jesus in His divine nature also share in that death? Did "God" die on the cross, or did just a man die on the cross?

We Lutherans confess with St. Peter, who, preaching to the Jews following Pentecost, accused them by identifying the Man who died on the cross according to His divinity, saying, “You have killed the

Prince of Life” (

Ac 3:13-15). But how could an eternal God die, and yet still be eternal? Scripture doesn’t say – but it says most clearly both that God is eternal and that He shared in the experience of Christ’s death. Scripture teaches both, and we believe, teach and confess both. But look at the astounding consequences of this death, and the positively galvanizing reality of what St. Peter was preaching to his fellow Jews. Not only did Christ, by His death as man, pay the penalty of man’s sin,

finishing His work on behalf of mankind, His death as God

terminated the Old Covenant with Israel – for we know that the death of one or both parties to a covenant is the only condition which legally terminates it. What St. Peter was preaching was that, no matter how the Jews or anyone else looks at the situation, there is absolutely no hope for them in the Old Covenant. None whatsoever. The work is finished, and the manner of its completion leaves no doubt regarding the status of that covenant, since the completion of Christ’s work also supplies the legal criteria for its termination. Rather, their only hope is in the “New Testament,” or the new promise, of the Man Who in His human body lived perfectly under God’s Law, Whose precious blood was shed as a propitiation for the sins of the World, and Who, by His Resurrection, showed Himself to be the eternal God that He claimed to be, and Who now promises forgiveness of sins and righteous standing before God to those who through faith receive them. This teaching gives no quarter to Dispensationalism, or any other system of belief which tries to retain a special arrangement between God and the Jews, for “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” (

Ga. 3:28).

They differ regarding the presence of Christ in the Eucharist

And this “New Testament” was exactly what Luther and Zwingli debated at Marburg. Christ, in the night in which He was betrayed, took bread, and when He had given thanks, broke it saying, “Take, eat; this

is My body, which

is given for you. Do this in remembrance of Me” (

Lk. 22:19; Mt. 26:27; Mk. 14:22; 1 Co. 11:24). In the same manner also He took the cup when He had supped, and when He had given thanks, He gave it to them, saying, “Drink ye all of it; this cup

is the

New Testament in My Blood, which

is shed for you for the remission of sins. This do, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of Me” (

Lk. 22:20; Mt. 26:28; Mk. 14:23-24; 1 Co. 11:25). This “New Testament” offered by Christ in His Blood, was a specific kind legal arrangement that is common in probate law even to this day. Luther, who was trained as a lawyer before entering the Augustinian Order, knew very well the ancient principles involved, and we are informed in great detail by his contemporaries why it was that Luther held so strictly to the very words of institution: Christ, in using this phraseology, was offering his “

last will and testament.” Very fitting, given that He knew that He was going to die on the cross the very next day. What this means for the bequeathed, if they would benefit from the Testator’s will, is that, if it is established that the Testator was of sound mind when He issued His will, and if the words coherently express the Testator’s wishes, the words

must be followed precisely and to the letter – even if they sound unreasonable. This in order that the will of the deceased may actually be honored. For example, if Uncle Felix bequeathed to his nephew Horace his entire estate, on the condition that Horace hop on his right leg three miles into town, bark like a dog for five minutes in the town square, and then hop on his left leg back home, that means that if Horace wants his inheritance, he had better get hopping – the will of Uncle Felix is clear, even if it makes no sense why Horace needs to do what is requested of him in order to receive his inheritance. In other words, the objections of reason against the clear will of the Testator are invalid.

Jesus Christ is the Testator of the New Testament (

He. 9:14-17). “Do

this” was the clear instruction that Christ gave as He issued His “last will and testament”; and in “doing this,” it is clear that we are to regard the bread and wine as not only bread and wine, but as Body and Blood – as the very Body and Blood that

was given and shed. But how can bread and wine also be Body and Blood? We Lutherans don’t claim to know. But we are quite certain that the same God Who can speak the universe into existence, Who can also pull off the Incarnation and the Virgin Birth, can, by His command and institution, also manage the sacramental union of His Body and Blood with the elements of the Eucharist. The question isn’t

how can this be? but

what do the Scriptures say?:

This cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ? For we being many are one bread, and one Body; for we are all partakers of that one Body (1 Co. 10:16-17).

But what are the implications of this teaching for the Lutheran communicant? They are

quite significant. Jesus Christ, in His human body, lived a perfect life under God’s Law. In this perfect body, He became sin for our sake, taking on the sin of the World, and suffering sin’s penalty – death and separation from God. The perfect Blood He shed in His death for our sin, was considered by God to be sufficient payment for the World’s sin, for the sin of each individual. He was found to be Just in the sight of God, and returned to life. When the Lutheran communicant receives the consecrated bread and wine in the Holy Supper, he is not merely partaking in a “meal of remembrance”. Rather, Christ Himself physically comes to the communicant and gives Himself to him. The Lutheran communicant is actually physically united with the perfect

Body of Christ, which lived perfectly in the sight of God under His Law and continues its perfect existence in the presence of God. The Lutheran communicant is actually united with the

Blood of Christ, which was declared by God to be Just payment for his sins. Thus united with Christ, the Lutheran stands united with those communicants who have likewise received Christ’s Body and Blood; and together they stand before God in the work and righteousness of Christ – their sin is atoned for and they are fully righteous in the sight of God. And this is our

inheritance as sons of God, is it not? There is no more personal, more intimate assurance of our “remission of sins” than this, for in the Holy Supper, the Logos, the Word of Forgiveness Himself, is physically united with us.

Zwingli objected, “Christ physically ascended into heaven, therefore He is physically present only in heaven. He cannot be present in heaven and also be present here on earth, in the Eucharist, as well. Therefore, we can say only that He is

spiritually present in the bread and wine.” Calvin concurred with this, though attempted a mediating position between Zwingli and Luther, claiming that the communicant, as he receives the bread and wine, is transported to heaven where the body of Christ is located, and is united with Him there,

apart from the bread and wine. We Lutherans agree that Christ bodily ascended and is present locally in heaven. But this is not the limit of His bodily presence. Responding with Scripture to Zwingli’s objection, we confess: “Christ fills

all” (

Ep. 1:18-23; 4:9-10). Further, there is no basis in the testimony of Scripture for dividing the natures of Christ or separating His divine from His human attributes, while there is every reason to require that they remain united: “the Word became flesh” (

Jn. 1:1-5,14) and “the

fullness of God dwelt in Him

bodily” (

Co. 2:9). Therefore, we conclude with Scripture that Christ

fills all in His human, as well as His divine natures; and if Christ can fill the whole universe, He can also be physically present in the bread and wine. Likewise, we can also trust His promise, “

I am with you always, even to the end of the world” (

Mt. 28:20), and believe that He is actually here with us.

They differ regarding Grace, and the Means by which the sinner gains access to it unto Salvation

But Zwingli also countered, “The physical is incompatible with the spiritual.” That is to say, divine perfection can have no part with the “fallen matter” that makes up the physical world, since it is infected with sin. Calvin concurred. Not only did this notion impact their formulations regarding the presence of Christ in the Eucharist, it also lies at the root of some

very serious differences between Reformed and Lutheran doctrines. The Reformed teach a doctrine called

Immediate Grace, that is, that

God works apart from means of any sort, that He works

directly in an individual, strictly apart from any means, to bring him to Salvation. We Lutherans, on the other hand, teach that God the Holy Spirit works to produce and strengthen saving faith

only through the Gospel, and the Gospel comes to man

only through means. We call them the

Means of Grace, and have identified

three such means appointed by God in His Holy Word, through which He works:

- the Word of God (which was “written that we might believe,” Ro. 10:17; Jn. 20:31)

- the Sacrament of Holy Communion (given “for the remission of sins,” Mt. 26:28), and

- the Sacrament of Holy Baptism (which is “for the remission of sins” and which “does save us,” Ac. 2:38; 22:16; 1 Pe. 3:18-22)

Thus, in response to Calvin and Zwingli, we Lutherans answer,

not only does the Bible state directly that God works through the Gospel in Word and Sacrament to create and strengthen faith, we can find no evidence in Scripture that He works apart from these Means. Sure, our reason tells us that since the Scriptures say God is sovereign and omnipotent, He can do any thing He wants, any time He wants, any way He wants. But this, alone, is of no comfort to the Christian at all, who wants

assurance of God’s working in himself, and wants to direct others to God where He can be found.

“How do I know that God is at work in

me?” This question becomes all the more critical when we consider another teaching regarding Grace that is espoused in Reformed doctrine:

Particular Grace. In this teaching, we are told that God, in His sovereignty, has turned His gracious countenance toward only some, and not others, that God does not love all sinners equally, and that as a result, He did

not come to atone for the sins of all mankind, but only for the sins of some. Thus, the Reformed also teach,

Limited Atonement. After all, Hell

will be populated, and it would place limitations on God’s omniscience if we were to assume that He did not know beforehand who would populate it! If He knew beforehand, then certainly it is reasonable to conclude that God’s sovereign plan of salvation was limited to only some, that His saving Grace was reserved for particular persons and not others. This leaves the poor Christian wondering if he were one of those God had chosen at the foundation of the world; and without the comfort of objective means through which he is promised that the Holy Spirit will work in him, he is left to look within himself, searching for evidence that he is among God’s elect. The consequence is that Reformed preaching tends to equip the believer for this task, by focusing on issues of

Sanctification.

Lutherans, on the other hand, do

not teach that Grace is “particular” or that Christ’s atoning work was “limited” to some, but not to others. Instead, we confess what the Scriptures directly say, and teach

Universal Grace (

Jn. 3:16) and

Universal Atonement (

1 Jn. 2:2; Co. 1:19-22). Moreover, because the Scriptures teach that the Holy Spirit is present and working through the Gospel in Word and Sacrament, the Lutheran is confident that (a) since God loves

all people, (b) since God atoned for the sins of

all people, and (c) since God works to produce and strengthen faith through His appointed Means, then (d) the Christian can confidently seek God

outside of himself, placing his trust in the objective promises of the Gospel, knowing that the Gospel is intended for him, and that God is at work through it to save him and to keep him as His own; and (e) the Christian can confidently preach this same message to unbelievers, knowing that He is faithful to work through His appointed Means to produce faith and thereby bring the unbeliever from death into life as His own dear child. The consequence is that true Lutheran preaching dwells, not on subjective themes of Sanctification, but on the objective message of Law and Gospel, on the message of

Justification by Faith Alone.

They differ regarding PredestinationThis is

the one big difference that everyone likes to start with when discussing the differences between Reformed and Lutheran teaching. I thought it best to end with this particular teaching in my little summary of theological differences, in order to display in leading up to it the Lutheran attitude toward the authority of Scripture and the role of reason relative to it. Obviously, we Lutherans are not unaware of the challenges reason hurls at our body of teaching. Calvin himself was rather merciless in his criticism of Luther, and Lutheran doctrine, declaring us guilty of “stupefying irrationalities.” Yeah, we get it. Nevertheless, we consider it safer to stand on the very word of God, than to deviate from it in either “jot or tittle.”

Predestination, or “Election to Grace,” is a biblical teaching. Both Reformed and Lutherans teach this doctrine. Scripture refers to those who have faith as the elect (

Ep. 1:3-14; 2 Th. 2:13-14), as those chosen by God at the foundation of the World. However, we Lutherans are quick to point out that

2 Th. 2:13-14 makes clear this election to grace was not a naked decree, but includes in the eternal act of God’s choosing the Means and process through which one’s election is made sure – “through sanctification of the Spirit and belief of the truth” (v13). That is, God’s choosing of His elect included the preaching of the Gospel and the work of the Holy Spirit through the Gospel to create faith in the heart of its hearer.

In addition to “Election to Grace,” Reformed Calvinists also teach that, as a consequence of God’s Sovereign omniscience, He also predestined some to Hell. This teaching is called “Election to Reprobation,” and it is a teaching rejected by Lutherans. It is nowhere stated in Scripture. Some Reformed authors will cite

Jude 4, Romans 9:17-24, or 1 Peter 2:8 in support of this doctrine, but upon close examination it is found that these verses fail to teach this doctrine. In

Jude 4,

prographo (“before … ordained”) is not a reference to ancient or eternal decree and is never used in this sense in any of the other places it is used in the New Testament (like

Ro. 15:4; Ga. 3:1; Ep. 3:3), but is used to indicate

writing beforehand, and probably refers to those St. Peter warned of in

2 Peter 2:3, given that Jude writes after St. Peter to the same audience, describing the same people that St. Peter warned of. Likewise, use of

1 Peter 2:8, “whereunto also they were appointed”, ignores the context, that such appointment is the

consequence of their rejection of the Gospel, not

antecedent to it.

By far,

Romans 9:17-24 seems to be given the greatest weight by Reformed commentators defending “Election to Reprobation.” Often, however, the difference between “fitted for destruction” (v22) and “afore prepared unto glory” (v23) is glossed over. Those vessels “fitted for destruction” were so fitted as a

consequence of their rejection of God’s repeated and long-suffering overtures of grace toward them,

not antecedent to their rejection. On the other hand, those “afore prepared unto glory” are so prepared from eternity, consistent with the doctrine of predestination that Lutherans and the Reformed agree to.

We Lutherans confess that Scripture teaches Predestination, or “Election to Grace,” but that it does not teach “Election to Reprobation.” Rather, we confess that Scripture teaches it is God’s

antecedent will that all men be saved (

1 Ti. 2:3-6 – God’s will from eternity for all mankind), but it is His

consequent will that those who reject Him suffer damnation (God’s will in response to an individual’s rejection of His grace, not from eternity). “Double Predestination” or “Election to Reprobation” is the Reformed Calvinist’s way of reconciling what appears to be divine paradox – that (1) it is God’s eternal will that

all men be saved, and (2) not everyone will be saved – and is accomplished by qualifying the word “

all” as “

all those He came to save.” The way of the Reformed Arminian is to elevate the role of the human in his own salvation, by making him a co-operator through his own will and intellectual assent. The Bible speaks against this as well. In

John 1:13 it makes clear that the will and decision of man is not involved; and the

second chapter of 1 Corinthians clearly teaches that man’s intellect is of no aid to him in understanding the things of God (for to him it is all foolishness), but that God’s truth must be taught to him by the Holy Spirit, apart from Whom true knowledge of God is impossible.

The fact is, all attempts to harmonize the statements of Scripture regarding election result in two errors. The first error is that statements not contained in Scripture are held up as Scripture's doctrine (i.e., God predestines some to hell [Calvinist], or, man co-operates in his own salvation [Arminian]). The second is that clear and direct statements of Scripture are rejected (i.e., it is not God’s will that

all mankind be saved [Calvinist], or, there is no eternal election [Arminian]). Further, the Holy Spirit has offered no harmonization of these statements in His Word. So how do we Lutherans handle this? First, we believe, teach and confess that it is God’s will that

all mankind be saved – His gracious countenance shines on all mankind. Second, we believe, teach and confess that Hell is a real place, prepared for the Devil and his angels, and that those who obstinately reject the gracious overtures of God in the promises of His Gospel, will spend an eternity in that place, separated from God forever. In other words, the Bible teaches both that God wants all people to be saved, and that Hell will be populated. The Bible teaches both. We believe both. And we leave it at that – accepting these statements of Scripture as they stand and leaving them unresolved.

ConclusionThe Renaissance, they say, was the bridge from the Mediæval period to the Modern period of Western history. From the Renaissance, Luther

faced backward in time, looking through history to the teaching of the Apostles. Though benefiting from the Renaissance humanism and classical learning of his time, he was square within a Mediæval frame of mind, fully comfortable with the mysteries placed before him in the clear and certain testimony of Scripture. To this day, genuine Lutheran theology retains this distinctly Mediæval character, comfortable, as we stand on the direct positive statements of Scripture, with the divine mysteries of the person of Christ, His presence in the Eucharist, or the work of the Holy Spirit through the Means of Grace, and as we continue to move into the future by facing the past, by looking through the Reformation to the teachings of the Apostles, and by retaining the historic and Scriptural practices of the Church which have given expression to those teachings over the millenia. Zwingli and Calvin, on the other hand, were building toward a future of Modernism. With Scripture as foundation, they faced

forward in time from the Renaissance into an unknown in which human reason would be king. Now that Modernism has passed into history, now that Materialistic Rationalism is itself flailing violently near the throes of death, now that we are entering into a

Postmodern Era, it will be interesting to see the impact of these two similar, yet divergent, “systems of protestant theology.” Will they continue to retain their character?

If any of the Lutheran teachings discussed above are of interest to the lay-reader, I supply the following list of books for further investigation:

Human Reason:

Christology

Law and Gospel

The Lord’s Supper:

Baptism:

Sanctification and Christian Works:

Doctrinal Unity in the Church:

Lutheran Confessions, Theology, and Practice:

Finally, if you’re interested in what confessional Reformed and Lutheran dialogue sounds like, a good radio program to listen to is

The White Horse Inn Classic, a program in the weekly line-up of

Pirate Christian Radio.

On Wednesdays through the Lenten Season this year (2013), we published sermons from Dr. Adolph Hoenecke (1835-1908), who is among the most important theologians of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), and from Dr. Paul E. Kretzmann (1883-1965), a prolific author, educator, historian and theologian of the Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod (LCMS) and among the more significant figures of 20th Century American Lutheranism. We will do the same through Holy Week. Except for today, Maundy Thursday. Instead of Dr. Hoenecke and Dr. Kretzmann, we will hear from Dr. Martin Luther himself, from his Hauspostille.

On Wednesdays through the Lenten Season this year (2013), we published sermons from Dr. Adolph Hoenecke (1835-1908), who is among the most important theologians of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), and from Dr. Paul E. Kretzmann (1883-1965), a prolific author, educator, historian and theologian of the Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod (LCMS) and among the more significant figures of 20th Century American Lutheranism. We will do the same through Holy Week. Except for today, Maundy Thursday. Instead of Dr. Hoenecke and Dr. Kretzmann, we will hear from Dr. Martin Luther himself, from his Hauspostille.