The term “Christmas”

The term “Christmas”The word “Christmas” comes from the Old English term Cristes Maesse, or the “Mass of Christ,” first found recorded in A.D. 1038. In Dutch it is “Kerst-misse,” and in Latin “Dies Natalis,” from which we get the French word “Noël.” In Italian it is “Il natale;” but in German “Weihnachtsfest,” named for the sacred vigil which takes place the night before Christmas. The word “Yule” simply comes from the Anglo-Saxon word “geol,” or feast, which was also the name of their month in which this feast took place. In Icelandic the term is “iol,” a feast still celebrated there each year in December.

As far as we can tell, Christmas as an observance of the birth of Jesus Christ, was not celebrated during the first hundred years of the Christian Church. The first evidence of the feast comes from Egypt. Sometime just before A.D. 200, Clement of Alexandria said that some Egyptian theologians set the year and the day of Christ’s birth, placing it on 25th day of the Egyptian month Pachon, or our May 20th, in the twenty-eighth year of Caesar Augustus. However, Clement also tells us that the Basilidians celebrated the Epiphany, and with it, the Nativity, most often on 11 Tybi, or our January 6th. Indeed, this double celebration became quite popular, partly because the appearance to the shepherds was seen as a manifestation of Christ’s glory, with the other being the worship of Magi from the East, which was already observed on that day. The December feast day did not reach the rest of the Church in North Africa until around the Third Century A.D.

When Was the first “Year of Our Lord?”

When was Jesus born? According to the present system of reckoning time, Jesus was born on December 25th before the year 1 (thus 1 B.C. as there is no year “zero”), or 754 years after the founding of Rome. This system was introduced by the Roman abbot, Dionysius Exigius in the Sixth Century, and is therefore called the “Dionysian System.” It was first used in historical writings in the Eighth Century by The Venerable Bede. Shortly after this, it was given official sanction in public documents by the French king Pepin the Short, and later by his son, Charlemagne. However, nearly all theologians are generally agreed that the year is not correct. The majority of the theologians of our day have accepted the year 749 or the early part of 750, four or five years before our era. This is based on the following facts:

- Jesus was born, according to both Matthew and Luke, before the death of Herod the Great. King Herod died during the 37th year after he had been appointed in Rome to rule over Judea. Thus his coronation took place in the Roman year 714. (Romans marked years from the founding of the City of Rome, which in our calendar took place in 753 B.C.) It was the Jewish custom that the royal years should always be counted from the 1st of Nisan (usually corresponding to our month of April), the first month of their religious year. Thus, his 37th year makes it’s beginning on the 1st of Nisan, 750, and runs to 751. Therefore Herod died in 750 or 751, four or five years previous to the present era. And since Herod ordered all the infant males in Bethlehem killed who were less than two years of age, Jesus would have to have been born in late 749 or very early in 750, that is, 5 or 4 B.C.

- The Jewish historian Josephus states that an eclipse of the moon took place shortly before the death of Herod. Astronomers have established that this happened in the night of March 12 to 13, 750. The death of Herod therefore falls in the latter part of March or early in April 750. At that time Jesus was already born, and as His circumcision, the Presentation in the temple, the visit of the wise men, and the slaughter of the innocents in Bethlehem belong between these two events, there must be a reasonable interval before the death of Herod. Herod died shortly after the murder of the children in Bethlehem. Jesus must have been born, then, in the final days of 749 or early in 750.

- In John 2: 19-20, we are told that when Jesus was in Jerusalem for His first Passover after His own baptism, He said, “Destroy this temple...” after which the Jews answered Him, “Forty and six years was this temple in building...” The sanctuary was not at that time completed, and we know that the work of reconstruction was begun in the 18th year of the reign of Herod.

The first year Herod actually ruled in Judea came in 717, the 18th year then falls between 734 and 735. The year of this visit of Christ to Jerusalem must therefore be 780. Since Luke informs us that Jesus was about thirty years of age when He commenced His ministry shortly after His baptism (Luke 3:23), we therefore come once again to late 749 as the year of His birth.

The first year Herod actually ruled in Judea came in 717, the 18th year then falls between 734 and 735. The year of this visit of Christ to Jerusalem must therefore be 780. Since Luke informs us that Jesus was about thirty years of age when He commenced His ministry shortly after His baptism (Luke 3:23), we therefore come once again to late 749 as the year of His birth. - Luke 3:1 contains the account of John the Baptist and of his appearance as the Forerunner of Christ. According to his report, the activity of John dates from the 15th year in the rule of Tiberius. The emperor Augustus died August 19th, 767, and was succeeded on the throne by his stepson, Tiberius. However, we should note that Luke uses the word “hegemony,” not “monarchy,” when he mentions the fifteen years in the reign of Tiberius. The Roman historian, Tacitus, informs us that Augustus, in a manner consistent with Roman law, made Tiberius his co-ruler toward the close of 764 or in January 765. From that time on then Tiberius was also Caesar. The Baptist’s appearance upon the scene comes then in 779. After John had begun his work, Jesus came to him. Thus, we arrive at 779 as the year of Jesus’ baptism, which brings us yet again to the Winter of 749-750 as the time of His birth.

What Was the Month and Day of Christ’s Birth?

But, in which month and on what day was Jesus born? Our present system uses December 25th, as we all know. And this date was universally accepted in the Fourth Century by the Western Christian Church, while the Churches in the East observed either January 6th or 10th. According to the old Julian calendar, December 25th was the shortest day of the year, and referred to in Rome and elsewhere as “the birthday of the unconquerable sun” or Dies natatis invicti solis. After that day, the sun began to rise on the horizon, and the days began to lengthen once again. As Jesus is the light of the world, early believers felt it was eminently fitting that the day of His birth should also be December 25th. This date was first placed on record in Rome in connection with Christ’s birth in a chronicle dating from A.D. 354. The Christian writer Chrysostom said, “It is not yet ten years since this day (December 25) was made known. Even so, it is now just as seriously observed as if it has come to us from the beginning. It is very plain, according to the Evangelist [Luke], that Christ was born during the first census, and in Rome it is possible for anyone to deduce, with the aid of the public archives, when this came about. From persons who have intimate knowledge of these records and who still live in the city, we have obtained this day; for they who dwell there and who have kept the day in accordance with an age-long tradition have recently given us this information.” In writing on the 132nd Psalm of David, Augustine says, “John was born on June 24th, when the days already began to diminish; but the Lord was born December 25th in which the days began to lengthen; for John himself has said: ‘He must increase, but I must decrease (John 3:30).’”

But, in which month and on what day was Jesus born? Our present system uses December 25th, as we all know. And this date was universally accepted in the Fourth Century by the Western Christian Church, while the Churches in the East observed either January 6th or 10th. According to the old Julian calendar, December 25th was the shortest day of the year, and referred to in Rome and elsewhere as “the birthday of the unconquerable sun” or Dies natatis invicti solis. After that day, the sun began to rise on the horizon, and the days began to lengthen once again. As Jesus is the light of the world, early believers felt it was eminently fitting that the day of His birth should also be December 25th. This date was first placed on record in Rome in connection with Christ’s birth in a chronicle dating from A.D. 354. The Christian writer Chrysostom said, “It is not yet ten years since this day (December 25) was made known. Even so, it is now just as seriously observed as if it has come to us from the beginning. It is very plain, according to the Evangelist [Luke], that Christ was born during the first census, and in Rome it is possible for anyone to deduce, with the aid of the public archives, when this came about. From persons who have intimate knowledge of these records and who still live in the city, we have obtained this day; for they who dwell there and who have kept the day in accordance with an age-long tradition have recently given us this information.” In writing on the 132nd Psalm of David, Augustine says, “John was born on June 24th, when the days already began to diminish; but the Lord was born December 25th in which the days began to lengthen; for John himself has said: ‘He must increase, but I must decrease (John 3:30).’”Still, if Jesus was born in the dead of Winter, how would this be reconciled with the presence of shepherds in the field, keeping watch over their flocks by night? Those who have traveled in Palestine will testify that weather conditions may remain almost perfect through the month of December, and even far into January.Thus, there is no reason why the last month of 749 or first month of 750 should not be settled upon as the time of Jesus’ birth. This would be our 5 or 6 B.C. Yes, it sounds odd to have Jesus born five or six years “Before Christ,” but unless we want to add five or six years to the number of our current year, we’ll just have to tolerate this little anomaly.

The feast of Christ’s birth was brought into the official life of the Church and the Empire by Constantine as early as A. D. 330. The Christian historian, Epiphanius, writing in Cyprus near the end of the Fourth Century, asserts that Christ was born on January 6th, and the Christian churches in Mesopotamia observed the birth of the Savior thirteen days after the winter solstice; that is, January 6th. But in Cappadocia December 25th was already celebrated as the anniversary of Christ’s birth before 380. About 385 Cyril of Jerusalem asked Pope Julius I to assign the true date of the nativity “from census documents brought by Titus to Rome;” and using this information Julius assigned December 25th. Jerome, writing about 411, chastises the Christian churches in Palestine for observing Christ’s birthday on Epiphany rather than the now accepted December date. In Antioch in A.D. 386, St. Chrysostom tries to unite Antioch in celebrating Christ’s birth on the 25th of December. Indeed, a large part of the community had already observed this festival on that day for at least the previous ten years. In the West, he says, the feast was thus kept, and goes on to say this was no novelty; for from Thrace (Greece) to Cadiz (Spain) this feast was celebrated. Finally, he asserts with authority that the census papers of the Holy Family were still at that time in Rome and could be used to verify the date of this celebration. Unfortunately, these records are no longer extant, otherwise there would be no mystery.

The feast of Christ’s birth was brought into the official life of the Church and the Empire by Constantine as early as A. D. 330. The Christian historian, Epiphanius, writing in Cyprus near the end of the Fourth Century, asserts that Christ was born on January 6th, and the Christian churches in Mesopotamia observed the birth of the Savior thirteen days after the winter solstice; that is, January 6th. But in Cappadocia December 25th was already celebrated as the anniversary of Christ’s birth before 380. About 385 Cyril of Jerusalem asked Pope Julius I to assign the true date of the nativity “from census documents brought by Titus to Rome;” and using this information Julius assigned December 25th. Jerome, writing about 411, chastises the Christian churches in Palestine for observing Christ’s birthday on Epiphany rather than the now accepted December date. In Antioch in A.D. 386, St. Chrysostom tries to unite Antioch in celebrating Christ’s birth on the 25th of December. Indeed, a large part of the community had already observed this festival on that day for at least the previous ten years. In the West, he says, the feast was thus kept, and goes on to say this was no novelty; for from Thrace (Greece) to Cadiz (Spain) this feast was celebrated. Finally, he asserts with authority that the census papers of the Holy Family were still at that time in Rome and could be used to verify the date of this celebration. Unfortunately, these records are no longer extant, otherwise there would be no mystery.Is the Feast of Christmas Simply a Cover for a Pagan Holiday?

It is clear that the origin of Christmas did not come simply from the Roman festival of Saturnalia. True, the Emperor Aurelian, during his brief rule, tried to institute a lavish festival around the Birth of the Unconquered Sun, on December 25th, A.D. 274, borrowing heavily from the Mithras observances of Persia. He pushed this celebration in order to breathe new life into Roman idol-worship, which was already dying out. And Aurelian’s pronouncement came after Christians had already been associating this day with the birth of Christ for many decades in at least a few parts of the Empire. Indeed this “Sol Invictus” festival was almost certainly an attempt to create a pagan alternative to a date that was already of some significance to believers. Thus, Christians were not imitating the pagans, rather the pagans were imitating the Christians!

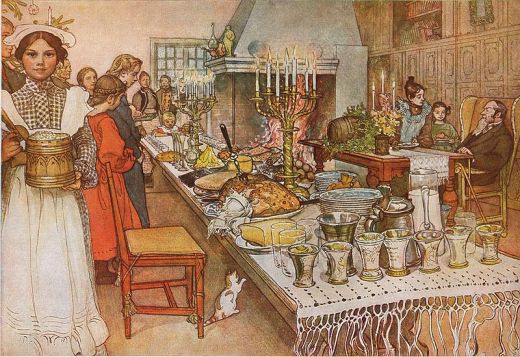

Feasting and Partying

This did not come from the Church. In fact, the Church attempted to impose strict discipline on this festival, and make it day of worship and contemplation. Emperor Theodoric, in A.D. 425, forbade Circus games on 25 December; though not until the time of Justinian III, in 529 is the cessation of all work imposed throughout the Empire on Christmas. The Council of Agde in 506 orders Holy Communion be celebrated on Christmas regardless of what day of the week it falls. The Second Council of Tours in 566 sets the sanctity of the “twelve days” from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of an Advent fast. Still, after that merry-making increased so much that the “Laws of King Cnut,” written around 1110, ordered a complete fast for all Christians from Christmas to Epiphany. In England, Christmas was forbidden by Act of Parliament in 1644; the day was to be a fast and a market day; shops were even compelled to be open on pain of a heavy fine; plum puddings and mince pies were condemned as indulgent and heathen. Even after the Restoration, Baptist and Puritan “Dissenters” continued to call Yuletide “Fooltide,” and refused to have anything to do with Christmas.

This did not come from the Church. In fact, the Church attempted to impose strict discipline on this festival, and make it day of worship and contemplation. Emperor Theodoric, in A.D. 425, forbade Circus games on 25 December; though not until the time of Justinian III, in 529 is the cessation of all work imposed throughout the Empire on Christmas. The Council of Agde in 506 orders Holy Communion be celebrated on Christmas regardless of what day of the week it falls. The Second Council of Tours in 566 sets the sanctity of the “twelve days” from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of an Advent fast. Still, after that merry-making increased so much that the “Laws of King Cnut,” written around 1110, ordered a complete fast for all Christians from Christmas to Epiphany. In England, Christmas was forbidden by Act of Parliament in 1644; the day was to be a fast and a market day; shops were even compelled to be open on pain of a heavy fine; plum puddings and mince pies were condemned as indulgent and heathen. Even after the Restoration, Baptist and Puritan “Dissenters” continued to call Yuletide “Fooltide,” and refused to have anything to do with Christmas.Christmas Pageants & Carols

The tradition of putting on dramatic, sometimes spectacular, displays of the various incidents of the Nativity began early in the Middle Ages. Often the Apostles and Martyrs would be included with Old Testament prophets, angels, kings, popes, and even well-known poets and artists in honoring Christ in these plays. In fact, the old adage, “To out-herod Herod”, that is, to over-act, dates from the often vivid depictions of Herod’s cruel violence in these plays.

The tradition of putting on dramatic, sometimes spectacular, displays of the various incidents of the Nativity began early in the Middle Ages. Often the Apostles and Martyrs would be included with Old Testament prophets, angels, kings, popes, and even well-known poets and artists in honoring Christ in these plays. In fact, the old adage, “To out-herod Herod”, that is, to over-act, dates from the often vivid depictions of Herod’s cruel violence in these plays.These plays also had a part in bringing about a great number of “noels,” and carols. Prudentius writes a hymn to the nativity in the Fourth Century, and Sedulius in the Fifth Century. The earliest German Weihnachtslieder date from the Eleventh and Twelfth centuries, the earliest French noels from the Eleventh, and the earliest English carols from the Thirteenth. “Adeste Fideles,” for example does not appear in its present form until the Seventeenth century. Most certainly however, these very popular tunes and words must have existed long before they were put down in writing.

Nativity Scenes or The “Crèche”

The word “crèche” comes from the French word for crib or cradle. St. Francis of Assisi in 1223 set up the first crèche outside of church. Normally these nativity scenes, some quite small, others actually life-size, were displayed only in churches, and mostly in the side altars. Almost immediately, however, these little replicas of the stable where Christ was born, along with the central characters of the story, became immensely popular in Christian homes and town squares throughout Europe. The presence of an ox and donkey were seen as a commentary on Isaiah 1:3 and Habakkuk 3:2, and they appear in the unique Fourth Century “Nativity” discovered in the St. Sebastian catacombs in 1877.

Christmas Tree

In the Thirteenth Century, Gervase of Tilbury wrote that in England grain was exposed on Christmas night to gain fertility from the dew which then falls. Indeed, the tradition that trees and flowers blossomed on this night is first quoted from an Arab geographer of the Tenth Century, and from there the story made it’s way to England. In a Thirteenth Century French story, candles are portrayed on a flowering tree. In England it was Joseph of Arimathea’s rod which was supposed to bloom at Glastonbury and elsewhere. Ivy, holly, mistletoe, and evergreen trees were all used by the ancient Druids as symbols of life in the dead of Winter. These were then appropriated by Christians for the same use.

In the Thirteenth Century, Gervase of Tilbury wrote that in England grain was exposed on Christmas night to gain fertility from the dew which then falls. Indeed, the tradition that trees and flowers blossomed on this night is first quoted from an Arab geographer of the Tenth Century, and from there the story made it’s way to England. In a Thirteenth Century French story, candles are portrayed on a flowering tree. In England it was Joseph of Arimathea’s rod which was supposed to bloom at Glastonbury and elsewhere. Ivy, holly, mistletoe, and evergreen trees were all used by the ancient Druids as symbols of life in the dead of Winter. These were then appropriated by Christians for the same use. From these various sources then came the practice of many types of greenery being used as decorations during the Christmas season. One of these customs developed into the Christmas tree. It is thought Martin Luther first brought an evergreen tree into the home and placed small candles on its branches to illustrate everlasting life coming from Christ, the Light of the World. However the first definite mention of such a tree is in 1605 at Strassburg. From there the custom entered the rest of France during the next century, and finally came to England in 1840 by way of the Prince Consort, Albert, the Lutheran husband of Queen Victoria.

“Xmas”

Well-meaning Christians sometimes bemoan the use of the letter “X” in place of Jesus’ title of “Christ” when used to designate the term “Christmas.” Almost every year lately there are emotional calls from believers to “keep Christ in Christmas!” Rest assured, the Savior is still very much in “Xmas.”

The letter ’X’ of the English alphabet closely resembles the Greek letter “chi,” which in that language gives a sound much like our English ’k,’ as in cholera or chrome. From very early in the Christian Church the first two Greek letters of the word “Christ,” were used as a symbol for the Redeemer. The Greek letter for the “r” sound, or “Rho,” looks like our English letter “p”. We see this combination in the symbol used in many church decorations which we call the “Chi-Rho;” what looks like an “X” and a “P” superimposed over one another.

The letter ’X’ of the English alphabet closely resembles the Greek letter “chi,” which in that language gives a sound much like our English ’k,’ as in cholera or chrome. From very early in the Christian Church the first two Greek letters of the word “Christ,” were used as a symbol for the Redeemer. The Greek letter for the “r” sound, or “Rho,” looks like our English letter “p”. We see this combination in the symbol used in many church decorations which we call the “Chi-Rho;” what looks like an “X” and a “P” superimposed over one another.Eventually, just the single letter “X” also came to represent Jesus Christ. This symbolism came to England with Christianity. As the Anglo-Saxon language grew into first Old English and then common English, it was considered very acceptable to abbreviate “Christ,” or “Jesus Christ” with either the Chi-Rho, or just the Chi or “X”. We can see this done frequently in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles beginning around A.D. 1050. This usage continued to be quite common through the Middle Ages, to the Victorian period, and of course is still used today. There was never any intention to do away with Jesus. “Xmas” means “Christmas,” period.

Santa Claus and Gift-giving

It is said that the origin for the mysterious benefactor of Christmas night: Knecht Ruprecht, Pelzmärtel on a wooden horse, St. Martin on a white charger, St. Nicholas, or Father Christmas, comes from Saints stepping into the shoes of the pagan god Oden, who, with his wife Frigga, descended during the nights between 25 December and 6 January on white horses to bless both earth and people. Welcoming fires were set on the hilltops, houses were adorned with many kinds of decorations and lights, work and trials suspended, and great feasts celebrated during these nights.

Indeed, it was quite common for peoples once they converted to Christianity to incorporate their one-time pagan deities into many of the customs and traditions of the new Christian Church. However, that is only part of the story, and it would not be fair not to give due acknowledgment to the individual most certainly more responsible than any other for the “Santa Claus” phenomenon, namely, Saint Nicholas of Myra.

As with many heroes of the early Christian Church; i.e. those that lived during that period of nearly three centuries before the faith could be practiced openly and without persecution; the life and works of Nicholas have acquired a great many myths and legends, some of them quite fantastic. In fact, one could say he is perhaps the most honored and venerated of any of Saints of this period. These facts we know: He was born about A.D. 270 at Patara in Lycia in the Roman province of Asia, now modern Turkey, to well-to-do Christian parents. Both his parents died in a plague when he was quite young and left him very wealthy, and he was raised by an uncle who was the Bishop of Patara. From very early in his childhood he was known for his piety and zeal for the Lord and the Church. He underwent severe hardship and imprisonment during the intense persecution of the Emperor Diocletian, but survived to see the legalization of the Christian faith during the rule of Constantine. When the office of Bishop at Myra, the provincial capital went vacant, the people persuaded him to take on this office, even though he was still quite young at the time. He was said to have attended the great Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325, and the story is that he walked right up to the arch-heretic Arius and slapped him in the face before the entire assembly. He is said to have died on December 6th, A.D. 343, in Myra, and buried there under the altar of his church. After the Muslim Saracens took over the area in the Eleventh Century, his bones were removed to the town of Bari in Italy, where they remain today.

As with many heroes of the early Christian Church; i.e. those that lived during that period of nearly three centuries before the faith could be practiced openly and without persecution; the life and works of Nicholas have acquired a great many myths and legends, some of them quite fantastic. In fact, one could say he is perhaps the most honored and venerated of any of Saints of this period. These facts we know: He was born about A.D. 270 at Patara in Lycia in the Roman province of Asia, now modern Turkey, to well-to-do Christian parents. Both his parents died in a plague when he was quite young and left him very wealthy, and he was raised by an uncle who was the Bishop of Patara. From very early in his childhood he was known for his piety and zeal for the Lord and the Church. He underwent severe hardship and imprisonment during the intense persecution of the Emperor Diocletian, but survived to see the legalization of the Christian faith during the rule of Constantine. When the office of Bishop at Myra, the provincial capital went vacant, the people persuaded him to take on this office, even though he was still quite young at the time. He was said to have attended the great Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325, and the story is that he walked right up to the arch-heretic Arius and slapped him in the face before the entire assembly. He is said to have died on December 6th, A.D. 343, in Myra, and buried there under the altar of his church. After the Muslim Saracens took over the area in the Eleventh Century, his bones were removed to the town of Bari in Italy, where they remain today.Among the nearly countless stories of amazing miracles attributed to Nicholas, two stand out as explanations for why he became the model for Santa Claus. During a severe famine a man of Patara lost all his money and was about to lose his home and property. He had three daughters of marriage age, but because they had no dowry they had no prospects of finding husbands. The father planned, it is said, to force his daughters into prostitution so that the family could survive. Nicholas heard of his plans, and one night, tossed three bags of gold in though an open window where the daughters were sleeping. Finding the gold when they awoke the next morning, they now had their dowries and soon were married off successfully.

In some versions, the bags were given in three successive nights, or even years on the same date, and by some accounts the bags were thrown – where else – down the chimney. Another variant has the daughters wash out their stocking and hang them to dry, the gold bags landing in them to be found the next morning. All these variants were widely known throughout the Christian world as early as the A.D. 700s. Another story takes place during yet another famine. An innkeeper on an island just off the coast of Myra supposedly killed and butchered three little children, and put them in pickling barrels to sell them to unsuspecting guests. Visiting the island to give aid to the needy, Nicholas surmised the evil deed done by the innkeeper. He brought the children back to life and returned them to their parents, thus becoming seen as the special protector and benefactor to all children.

From these pious legends it is easy to see how Saint Nicholas could become so dear and important to people of many countries down through the centuries. That his “saint day” was so close to Christmas also lent itself to a close association between the two. Once we throw in various other aspects left over from early pagan sources, such as elves, reindeer, sleighs, coal, and the like, and stir the whole mixture together with an excuse for merry-making at the end of the year and the natural commercialism of free enterprise – viola! – Santa Claus!

Of course, Christian believers, should, can, and do filter out all this interference with their worship of the Christ-child, and the celebration of the great fact of Christmas, which is Immanuel – God with us! As the Apostle John writes so beautifully by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, “And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory, glory as of the Only Begotten from the Father, full of grace and truth.” (John 1:14)

Of course, Christian believers, should, can, and do filter out all this interference with their worship of the Christ-child, and the celebration of the great fact of Christmas, which is Immanuel – God with us! As the Apostle John writes so beautifully by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, “And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory, glory as of the Only Begotten from the Father, full of grace and truth.” (John 1:14)A very blessed and joyous Christmas to one and all!

Pastor Spencer

[Once again, no claim is made for originality in this material. It has been collected from many sources over many years, for the benefit of my local congregation.]

1 comment:

Thanks for the timely and well-researched information. I, personally, have never met a Jew or anyone of other faith that has been offended when I wish them a "Merry Christmas". It seems to be the secular humanists who object and attempt to redefine Christmas.

Merry Christmas to all, and praise the Lord for his greatest gift to us, our Savior Jesus Christ!

Johan Spenglergeist

Post a Comment

Comments will be accepted or rejected based on the sound Christian judgment of the moderators.

Since anonymous comments are not allowed on this blog, please sign your full name at the bottom of every comment, unless it already appears in your identity profile.